Nov

2020

Information Overload Fake News Social Media

Information Overload Helps Fake News Spread, and Social Media Knows It

Understanding how algorithm manipulators exploit our cognitive vulnerabilities empowers us to fight back

a minefield of cognitive biases.

People who behaved in accordance with them—for example, by staying away from the overgrown pond bank where someone said there was a viper—were more likely to survive than those who did not.

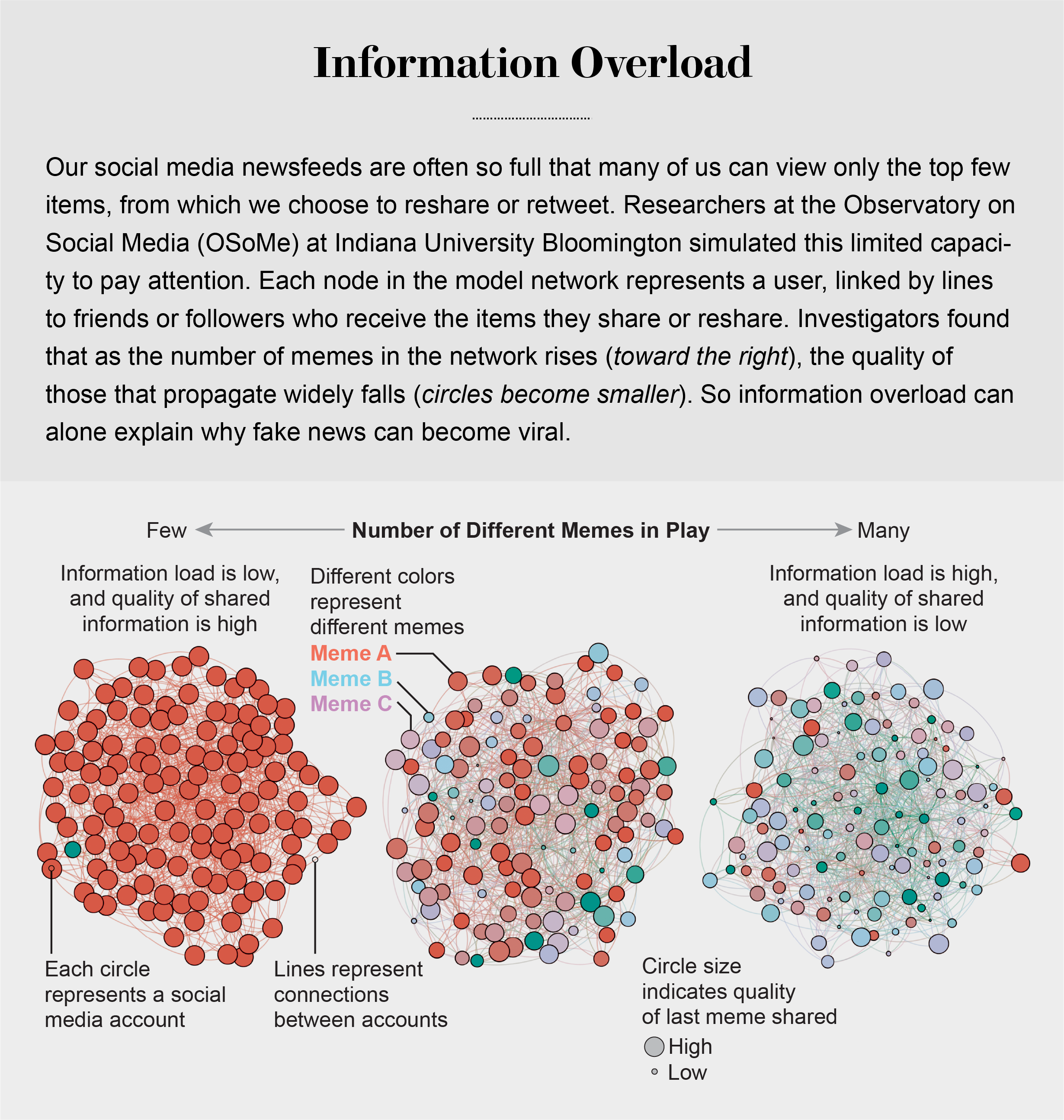

Compounding the problem is the proliferation of online information. Viewing and producing blogs, videos, tweets and other units of information called memes has become so cheap and easy that the information marketplace is inundated. My note: folksonomy in its worst.

At the University of Warwick in England and at Indiana University Bloomington’s Observatory on Social Media (OSoMe, pronounced “awesome”), our teams are using cognitive experiments, simulations, data mining and artificial intelligence to comprehend the cognitive vulnerabilities of social media users.

developing analytical and machine-learning aids to fight social media manipulation.

As Nobel Prize–winning economist and psychologist Herbert A. Simon noted, “What information consumes is rather obvious: it consumes the attention of its recipients.”

attention economy

Our models revealed that even when we want to see and share high-quality information, our inability to view everything in our news feeds inevitably leads us to share things that are partly or completely untrue.

Frederic Bartlett

Cognitive biases greatly worsen the problem.

We now know that our minds do this all the time: they adjust our understanding of new information so that it fits in with what we already know. One consequence of this so-called confirmation bias is that people often seek out, recall and understand information that best confirms what they already believe.

This tendency is extremely difficult to correct.

Making matters worse, search engines and social media platforms provide personalized recommendations based on the vast amounts of data they have about users’ past preferences.

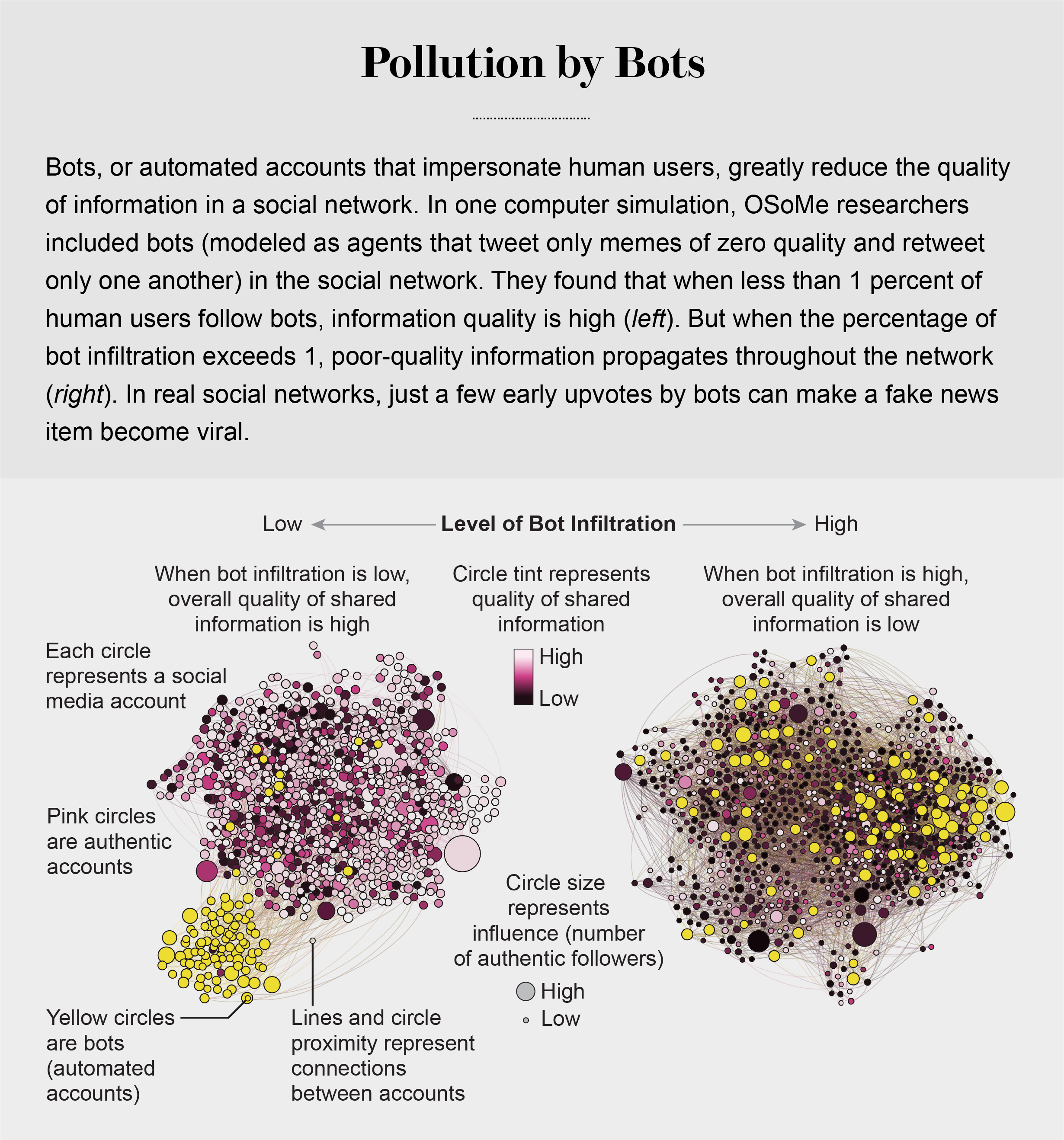

pollution by bots

Social Herding

social groups create a pressure toward conformity so powerful that it can overcome individual preferences, and by amplifying random early differences, it can cause segregated groups to diverge to extremes.

Social media follows a similar dynamic. We confuse popularity with quality and end up copying the behavior we observe.

information is transmitted via “complex contagion”: when we are repeatedly exposed to an idea, typically from many sources, we are more likely to adopt and reshare it.

In addition to showing us items that conform with our views, social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and Instagram place popular content at the top of our screens and show us how many people have liked and shared something. Few of us realize that these cues do not provide independent assessments of quality.

programmers who design the algorithms for ranking memes on social media assume that the “wisdom of crowds” will quickly identify high-quality items; they use popularity as a proxy for quality. My note: again, ill-conceived folksonomy.

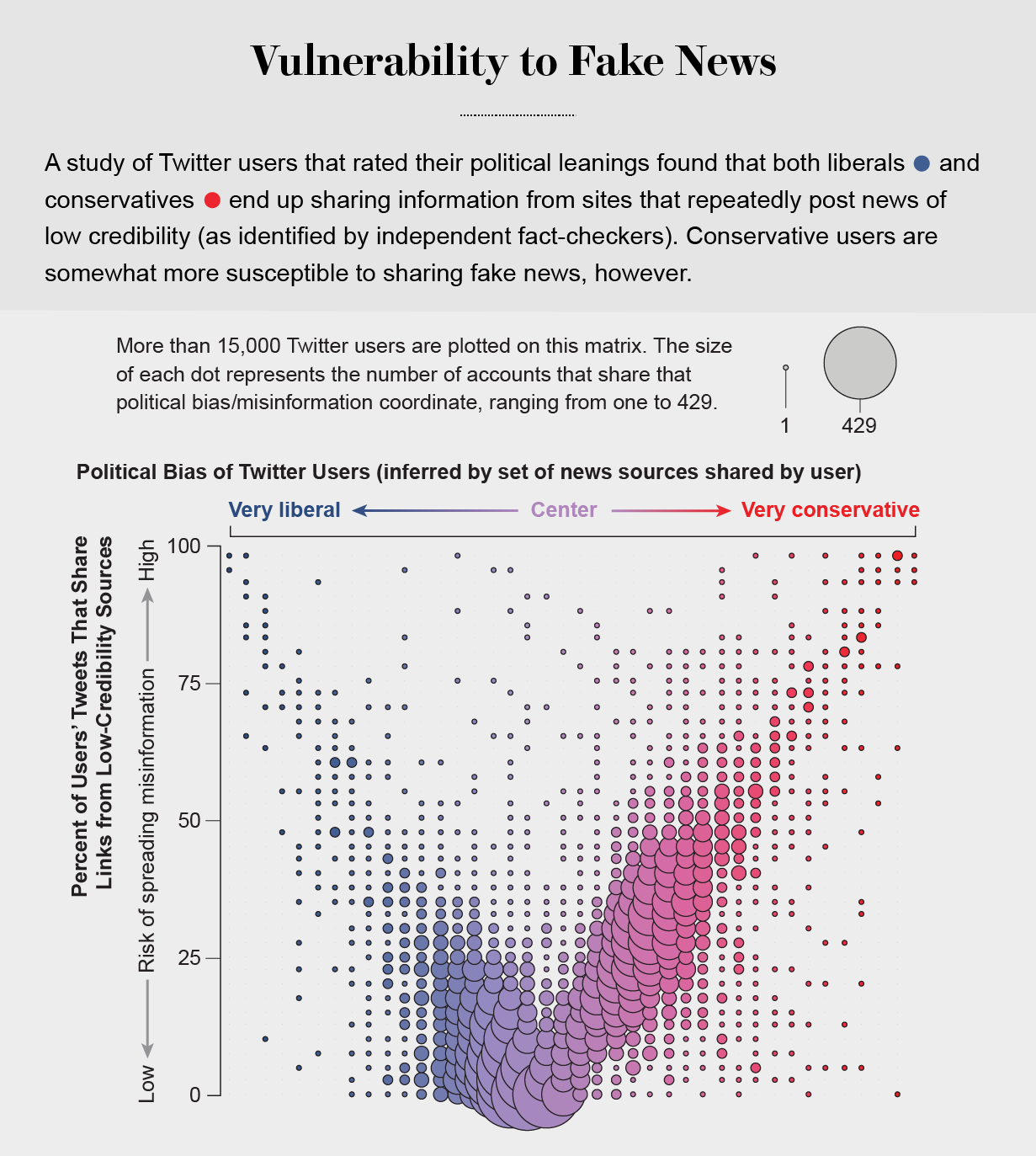

Echo Chambers

the political echo chambers on Twitter are so extreme that individual users’ political leanings can be predicted with high accuracy: you have the same opinions as the majority of your connections. This chambered structure efficiently spreads information within a community while insulating that community from other groups.

socially shared information not only bolsters our biases but also becomes more resilient to correction.

machine-learning algorithms to detect social bots. One of these, Botometer, is a public tool that extracts 1,200 features from a given Twitter account to characterize its profile, friends, social network structure, temporal activity patterns, language and other features. The program compares these characteristics with those of tens of thousands of previously identified bots to give the Twitter account a score for its likely use of automation.

Some manipulators play both sides of a divide through separate fake news sites and bots, driving political polarization or monetization by ads.

recently uncovered a network of inauthentic accounts on Twitter that were all coordinated by the same entity. Some pretended to be pro-Trump supporters of the Make America Great Again campaign, whereas others posed as Trump “resisters”; all asked for political donations.

a mobile app called Fakey that helps users learn how to spot misinformation. The game simulates a social media news feed, showing actual articles from low- and high-credibility sources. Users must decide what they can or should not share and what to fact-check. Analysis of data from Fakey confirms the prevalence of online social herding: users are more likely to share low-credibility articles when they believe that many other people have shared them.

Hoaxy, shows how any extant meme spreads through Twitter. In this visualization, nodes represent actual Twitter accounts, and links depict how retweets, quotes, mentions and replies propagate the meme from account to account.

Free communication is not free. By decreasing the cost of information, we have decreased its value and invited its adulteration.