Caldwell, C. (April, 2017). Sending Jobs Overseas. CRB, 27(2).

http://www.claremont.org/crb/article/sending-jobs-overseas/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Claremont_Institute

Caldwell’s book review of

Baldwin, Richard E. The Great Convergence: Information Technology and the New Globalization. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2016. not at SCSU library, available through ILL (https://mplus.mnpals.net/vufind/Record/008770850/Hold?item_id=MSU50008770850000010&id=008770850&hashKey=cff0a018a46178d4d3208ac449d86c4e#tabnav)

Globalization’s cheerleaders, from Columbia University economist Jagdish Bhagwati to New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman, made arguments from classical economics: by buying manufactured products from people overseas who made them cheaper than we did, the United States could get rich concentrating on product design, marketing, and other lucrative services. That turned out to be a mostly inaccurate description of how globalism would work in the developed world, as mainstream politicians everywhere are now discovering.

Certain skeptics, including polymath author Edward Luttwak and Harvard economist Dani Rodrik, put forward a better account. In his 1998 book Turbo-Capitalism, Luttwak gave what is still the most succinct and accurate reading of the new system’s economic consequences. “It enriches industrializing poor countries, impoverishes the semi-affluent majority in rich countries, and greatly adds to the incomes of the top 1 percent on both sides who are managing the arbitrage.”

In The Great Convergence, Richard Baldwin, an economist at the Graduate Institute in Geneva, gives us an idea why, over the past generation, globalization’s benefits have been so hard to explain and its damage so hard to diagnose.

We have had “globalization,” in the sense of far-flung trade, for centuries now.

ut around 1990, the cost of sharing information at a distance fell dramatically. Workers on complex projects no longer had to cluster in the same factory, mill town, or even country. Other factors entered in. Tariffs fell. The rise of “Global English” as a common language of business reduced the cost of moving information (albeit at an exorbitant cost in culture). “Containerization” (the use of standard-sized shipping containers across road, rail, and sea transport) made packing and shipping predictable and helped break the world’s powerful longshoremen’s unions. Active “pro-business” political reforms did the rest.

Far-flung “global value chains” replaced assembly lines. Corporations came to do some of the work of governments, because in the free-trade climate imposed by the U.S., they could play governments off against one another. Globalization is not about nations anymore. It is not about products. And the most recent elections showed that it has not been about people for a long time. No, it is about tasks.

his means a windfall for what used to be called the Third World. More than 600 million people have been pulled out of dire poverty. They can get richer by building parts of things.

The competition that globalization has created for manufacturing has driven the value-added in manufacturing down close to what we would think of as zilch. The lucrative work is in the design and the P.R.—the brainy, high-paying stuff that we still get to do.

But only a tiny fraction of people in any society is equipped to do lucrative brainwork. In all Western societies, the new formula for prosperity is inconsistent with the old formula for democracy.

One of these platitudes is that all nations gain from trade. Baldwin singles out Harvard professor and former George W. Bush Administration economic adviser Gregory Mankiw, who urged passage of the Obama Administration mega-trade deals TPP and Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) on the grounds that America should “work in those industries in which we have an advantage compared with other nations, and we should import from abroad those goods that can be produced more cheaply there.”

That was a solid argument 200 years ago, when the British economist David Ricardo developed modern doctrines of trade. In practical terms, it is not always solid today. What has changed is the new mobility of knowledge. But knowledge is a special commodity. It can be reused. Several people can use it at the same time. It causes people to cluster in groups, and tends to grow where those groups have already clustered.

When surgeries involved opening the patient up like a lobster or a peapod, the doctor had to be in physical contact with a patient. New arthroscopic processes require the surgeon to guide cutting and cauterizing tools by computer. That computer did not have to be in the same room. And if it did not, why did it have to be in the same country? In 2001, a doctor in New York performed surgery on a patient in Strasbourg. In a similar way, the foreman on the American factory floor could now coordinate production processes in Mexico. Each step of the production process could now be isolated, and then offshored. This process, Baldwin writes, “broke up Team America by eroding American labor’s quasi-monopoly on using American firms’ know-how.”

To explain why the idea that all nations win from trade isn’t true any longer, Baldwin returns to his teamwork metaphor. In the old Ricardian world that most policymakers still inhabit, the international economy could be thought of as a professional sports league. Trading goods and services resembled trading players from one team to another. Neither team would carry out the deal unless it believed it to be in its own interests. Nowadays, trade is more like an arrangement by which the manager of the better team is allowed to coach the lousier one in his spare time.

Vietnam, which does low-level assembly of wire harnesses for Honda. This does not mean Vietnam has industrialized, but nations like it no longer have to.

In the work of Thomas Friedman and other boosters you find value chains described as kaleidoscopic, complex, operating in a dozen different countries. Those are rare. There is less to “global value chains” than meets the eye. Most of them, Baldwin shows, are actually regional value chains. As noted, they exist on the periphery of the United States, Europe, or Japan. In this, offshoring resembles the elaborate international transactions that Florentine bankers under the Medicis engaged in for the sole purpose of avoiding church strictures on moneylending.

One way of describing outsourcing is as a verdict on the pay structure that had arisen in the West by the 1970s: on trade unions, prevailing-wage laws, defined-benefit pension plans, long vacations, and, more generally, the power workers had accumulated against their bosses.

In 1993, during the first month of his presidency, Bill Clinton outlined some of the promise of a world in which “the average 18-year-old today will change jobs seven times in a lifetime.” How could anyone ever have believed in, tolerated, or even wished for such a thing? A person cannot productively invest the resources of his only life if he’s going to be told every five years that everything he once thought solid has melted into ait.

The more so since globalization undermines democracy, in the ways we have noted. Global value chains are extraordinarily delicate. They are vulnerable to shocks. Terrorists have discovered this. In order to work, free-trade systems must be frictionless and immune to interruption, forever. This means a program of intellectual property protection, zero tariffs, and cross-border traffic in everything, including migrants. This can be assured only in a system that is veto-proof and non-consultative—in short, undemocratic.

Sheltered from democracy, the economy of the free trade system becomes more and more a private space.

+#+#+#+#+#+#+#+#+#+#+#+#+#+#+#+#+#+#+#+

Caldwell, C. (2014, November). Twilight of Democracy. CRB, 14(4).

Caldwell’s book review of

Fukuyama, Francis. The Origins of Political Order: From Prehuman Times to the French Revolution. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011. SCSU Library: https://mplus.mnpals.net/vufind/Record/007359076 Call Number: JC11 .F85 2011

http://www.claremont.org/crb/article/twilight-of-democracy/

Fukuyama’s first volume opened with China’s mandarin bureaucracy rather than the democracy of ancient Athens, shifting the methods of political science away from specifically Western intellectual genealogies and towards anthropology. Nepotism and favor-swapping are man’s basic political motivations, as Fukuyama sees it. Disciplining those impulses leads to effective government, but “repatrimonialization”—the capture of government by private interests—threatens whenever vigilance is relaxed. Fukuyama’s new volume, which describes political order since the French Revolution, extends his thinking on repatrimonialization, from the undermining of meritocratic bureaucracy in Han China through the sale of offices under France’s Henri IV to the looting of foreign aid in post-colonial Zaire. Fukuyama is convinced that the United States is on a similar path of institutional decay.

Political philosophy asks which government is best for man. Political science asks which government is best for government. Political decline, Fukuyama insists, is not the same thing as civilizational collapse.

Fukuyama is not the first to remark that wars can spur government efficiency—even if front-line soldiers are the last to benefit from it.

Relative to the smooth-running systems of northwestern Europe, American bureaucracy has been a dud, riddled with corruption from the start and resistant to reform. Patronage—favors for individual cronies and supporters—has thrived.

Clientelism is an ambiguous phenomenon: it is bread and circuses, it is race politics, it is doing favors for special classes of people. Clientelism is both more democratic and more systemically corrupting than the occasional nepotistic appointment.

why modern mass liberal democracy has developed on clientelistic lines in the U.S. and meritocratic ones in Europe. In Europe, democracy, when it came, had to adapt itself to longstanding pre-democratic institutions, and to governing elites that insisted on established codes and habits. Where strong states precede democracy (as in Germany), bureaucracies are efficient and uncorrupt. Where democracy precedes strong states (as in the United States but also Greece and Italy), government can be viewed by the public as a piñata.

Fukuyama contrasts the painstaking Japanese development of Taiwan a century ago with the mess that the U.S. Congress, “eager to impose American models of government on a society they only dimly understood,” was then making of the Philippines. It is not surprising that Fukuyama was one of the most eloquent conservative critics of the U.S. invasion of Iraq from the very beginning.

What distinguishes once-colonized Vietnam and China and uncolonized Japan and Korea from these Third World basket cases is that the East Asian lands “all possess competent, high-capacity states,” in contrast to sub-Saharan Africa, which “did not possess strong state-level institutions.”

Fukuyama does not think ethnic homogeneity is a prerequisite for successful politics

the United States “suffers from the problem of political decay in a more acute form than other democratic political systems.” It has kept the peace in a stagnant economy only by dragooning women into the workplace and showering the working and middle classes with credit.

public-sector unions have colluded with the Democratic Party to make government employment more rewarding for those who do it and less responsive to the public at large. In this sense, government is too big. But he also believes that cutting taxes on the rich in hopes of spurring economic growth has been a fool’s errand, and that the beneficiaries of deregulation, financial and otherwise, have grown to the point where they have escaped bureaucratic control altogether. In this sense, government is not big enough.

Washington, as Fukuyama sees it, is a patchwork of impotence and omnipotence—effective where it insists on its prerogatives, ineffective where it has been bought out. The unpredictable results of democratic oversight have led Americans to seek guidance in exactly the wrong place: the courts, which have both exceeded and misinterpreted their constitutional responsibilities. the almost daily insistence of courts that they are liberating people by removing discretion from them gives American society a Soviet cast.

“Effective modern states,” he writes, “are built around technical expertise, competence, and autonomy.”

http://librev.com/index.php/2013-03-30-08-56-39/discussion/culture/3234-gartziya-i-problemite-na-klientelistkata-darzhava

#+#+#+#+#+#+#+#+#+#+#+#+#+#+#+#+#+#+#+#+#+

Williams, J. (2017, May). The Dumb Politics of Elite Condescension. NYT

https://mobile.nytimes.com/2017/05/27/opinion/sunday/the-dumb-politics-of-elite-condescension.html

the sociologists Richard Sennett and Jonathan Cobb call the “hidden injuries of class.” These are dramatized by a recent employment study, in which the sociologists Lauren A. Rivera and Andras Tilcsik sent 316 law firms résumés with identical and impressive work and academic credentials, but different cues about social class. The study found that men who listed hobbies like sailing and listening to classical music had a callback rate 12 times higher than those of men who signaled working-class origins, by mentioning country music, for example.

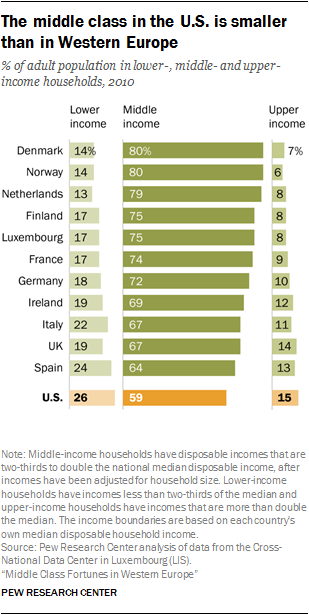

Politically, the biggest “hidden injury” is the hollowing out of the middle class in advanced industrialized countries. For two generations after World War II, working-class whites in the United States enjoyed a middle-class standard of living, only to lose it in recent decades.

The college-for-all experiment did not work. Two-thirds of Americans are not college graduates. We need to continue to make college more accessible, but we also need to improve the economic prospects of Americans without college degrees.

the United States has a well-documented dearth of workers qualified for middle-skill jobs that pay $40,000 or more a year and require some postsecondary education but not a college degree. A 2014 report by Accenture, Burning Glass Technologies and Harvard Business School found that a lack of adequate middle-skills talent affects the productivity of “47 percent of manufacturing companies, 35 percent of health care and social assistance companies, and 21 percent of retail companies.”

Skillful, a partnership among the Markle Foundation, LinkedIn and Colorado, is one initiative pointing the way. Skillful helps provide marketable skills for job seekers without college degrees and connects them with employers in need of middle-skilled workers in information technology, advanced manufacturing and health care. For more information, see my other IMS blog entries, such as: https://blog.stcloudstate.edu/ims/2017/01/11/credly-badges-on-canvas/