Key Issues in Teaching and Learning

https://www.educause.edu/eli/initiatives/key-issues-in-teaching-and-learning

A roster of results since 2011 is here.

1. Academic Transformation

2. Accessibility and UDL

3. Faculty Development

4. Privacy and Security

5. Digital and Information Literacies

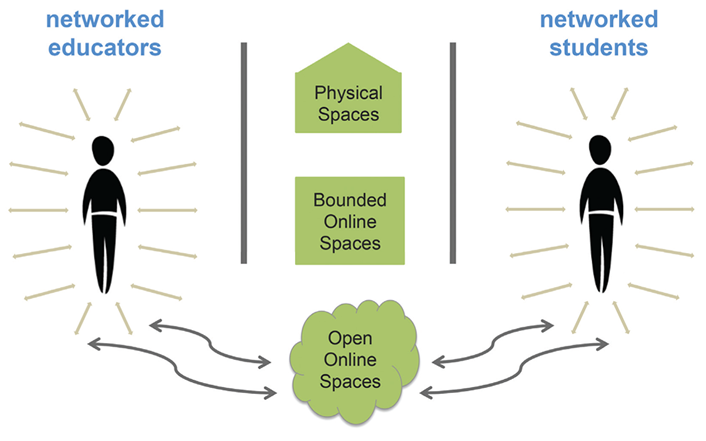

https://cdn.nmc.org/media/2017-nmc-strategic-brief-digital-literacy-in-higher-education-II.pdf

Three Models of Digital Literacy: Universal, Creative, Literacy Across Disciplines

United States digital literacy frameworks tend to focus on educational policy details and personal empowerment, the latter encouraging learners to become more effective students, better creators, smarter information consumers, and more influential members of their community.

National policies are vitally important in European digital literacy work, unsurprising for a continent well populated with nation-states and struggling to redefine itself, while still trying to grow economies in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent financial pressures

African digital literacy is more business-oriented.

Middle Eastern nations offer yet another variation, with a strong focus on media literacy. As with other regions, this can be a response to countries with strong state influence or control over local media. It can also represent a drive to produce more locally-sourced content, as opposed to consuming material from abroad, which may elicit criticism of neocolonialism or religious challenges.

p. 14 Digital literacy for Humanities: What does it mean to be digitally literate in history, literature, or philosophy? Creativity in these disciplines often involves textuality, given the large role writing plays in them, as, for example, in the Folger Shakespeare Library’s instructor’s guide. In the digital realm, this can include web-based writing through social media, along with the creation of multimedia projects through posters, presentations, and video. Information literacy remains a key part of digital literacy in the humanities. The digital humanities movement has not seen much connection with digital literacy, unfortunately, but their alignment seems likely, given the turn toward using digital technologies to explore humanities questions. That development could then foster a spread of other technologies and approaches to the rest of the humanities, including mapping, data visualization, text mining, web-based digital archives, and “distant reading” (working with very large bodies of texts). The digital humanities’ emphasis on making projects may also increase

Digital Literacy for Business: Digital literacy in this world is focused on manipulation of data, from spreadsheets to more advanced modeling software, leading up to degrees in management information systems. Management classes unsurprisingly focus on how to organize people working on and with digital tools.

Digital Literacy for Computer Science: Naturally, coding appears as a central competency within this discipline. Other aspects of the digital world feature prominently, including hardware and network architecture. Some courses housed within the computer science discipline offer a deeper examination of the impact of computing on society and politics, along with how to use digital tools. Media production plays a minor role here, beyond publications (posters, videos), as many institutions assign multimedia to other departments. Looking forward to a future when automation has become both more widespread and powerful, developing artificial intelligence projects will potentially play a role in computer science literacy.

6. Integrated Planning and Advising Systems for Student Success (iPASS)

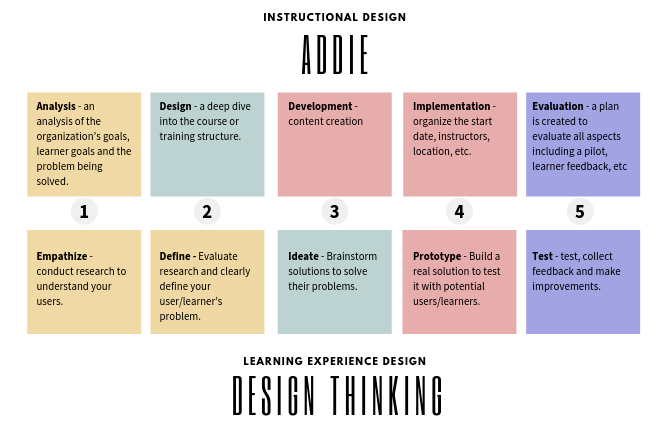

7. Instructional Design

8. Online and Blended Learning

In traditional instruction, students’ first contact with new ideas happens in class, usually through direct instruction from the professor; after exposure to the basics, students are turned out of the classroom to tackle the most difficult tasks in learning — those that involve application, analysis, synthesis, and creativity — in their individual spaces. Flipped learning reverses this, by moving first contact with new concepts to the individual space and using the newly-expanded time in class for students to pursue difficult, higher-level tasks together, with the instructor as a guide.

Let’s take a look at some of the myths about flipped learning and try to find the facts.

Myth: Flipped learning is predicated on recording videos for students to watch before class.

Fact: Flipped learning does not require video. Although many real-life implementations of flipped learning use video, there’s nothing that says video must be used. In fact, one of the earliest instances of flipped learning — Eric Mazur’s peer instruction concept, used in Harvard physics classes — uses no video but rather an online text outfitted with social annotation software. And one of the most successful public instances of flipped learning, an edX course on numerical methods designed by Lorena Barba of George Washington University, uses precisely one video. Video is simply not necessary for flipped learning, and many alternatives to video can lead to effective flipped learning environments [http://rtalbert.org/flipped-learning-without-video/].

Myth: Flipped learning replaces face-to-face teaching.

Fact: Flipped learning optimizes face-to-face teaching. Flipped learning may (but does not always) replace lectures in class, but this is not to say that it replaces teaching. Teaching and “telling” are not the same thing.

Myth: Flipped learning has no evidence to back up its effectiveness.

Fact: Flipped learning research is growing at an exponential pace and has been since at least 2014. That research — 131 peer-reviewed articles in the first half of 2017 alone — includes results from primary, secondary, and postsecondary education in nearly every discipline, most showing significant improvements in student learning, motivation, and critical thinking skills.

Myth: Flipped learning is a fad.

Fact: Flipped learning has been with us in the form defined here for nearly 20 years.

Myth: People have been doing flipped learning for centuries.

Fact: Flipped learning is not just a rebranding of old techniques. The basic concept of students doing individually active work to encounter new ideas that are then built upon in class is almost as old as the university itself. So flipped learning is, in a real sense, a modern means of returning higher education to its roots. Even so, flipped learning is different from these time-honored techniques.

Myth: Students and professors prefer lecture over flipped learning.

Fact: Students and professors embrace flipped learning once they understand the benefits. It’s true that professors often enjoy their lectures, and students often enjoy being lectured to. But the question is not who “enjoys” what, but rather what helps students learn the best.They know what the research says about the effectiveness of active learning

Assertion: Flipped learning provides a platform for implementing active learning in a way that works powerfully for students.

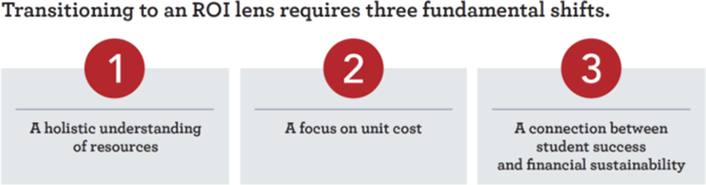

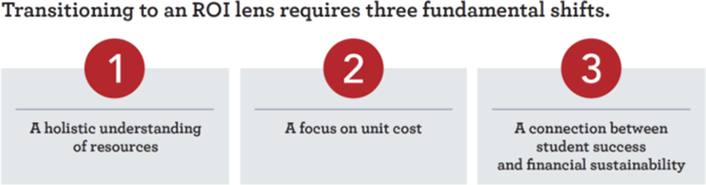

9. Evaluating Technology-based Instructional Innovations

What is the total cost of my innovation, including both new spending and the use of existing resources?

What’s the unit I should measure that connects cost with a change in performance?

How might the expected change in student performance also support a more sustainable financial model?

The Exposure Approach: we don’t provide a way for participants to determine if they learned anything new or now have the confidence or competence to apply what they learned.

The Exemplar Approach: from ‘show and tell’ for adults to show, tell, do and learn.

The Tutorial Approach: Getting a group that can meet at the same time and place can be challenging. That is why many faculty report a preference for self-paced professional development.build in simple self-assessment checks. We can add prompts that invite people to engage in some sort of follow up activity with a colleague. We can also add an elective option for faculty in a tutorial to actually create or do something with what they learned and then submit it for direct or narrative feedback.

The Course Approach: a non-credit format, these have the benefits of a more structured and lengthy learning experience, even if they are just three to five-week short courses that meet online or in-person once every week or two.involve badges, portfolios, peer assessment, self-assessment, or one-on-one feedback from a facilitator

The Academy Approach: like the course approach, is one that tends to be a deeper and more extended experience. People might gather in a cohort over a year or longer.Assessment through coaching and mentoring, the use of portfolios, peer feedback and much more can be easily incorporated to add a rich assessment element to such longer-term professional development programs.

The Mentoring Approach: The mentors often don’t set specific learning goals with the mentee. Instead, it is often a set of structured meetings, but also someone to whom mentees can turn with questions and tips along the way.

The Coaching Approach: A mentor tends to be a broader type of relationship with a person.A coaching relationship tends to be more focused upon specific goals, tasks or outcomes.

The Peer Approach:This can be done on a 1:1 basis or in small groups, where those who are teaching the same courses are able to compare notes on curricula and teaching models. They might give each other feedback on how to teach certain concepts, how to write syllabi, how to handle certain teaching and learning challenges, and much more. Faculty might sit in on each other’s courses, observe, and give feedback afterward.

The Self-Directed Approach:a self-assessment strategy such as setting goals and creating simple checklists and rubrics to monitor our progress. Or, we invite feedback from colleagues, often in a narrative and/or informal format. We might also create a portfolio of our work, or engage in some sort of learning journal that documents our thoughts, experiments, experiences, and learning along the way.

The Buffet Approach:

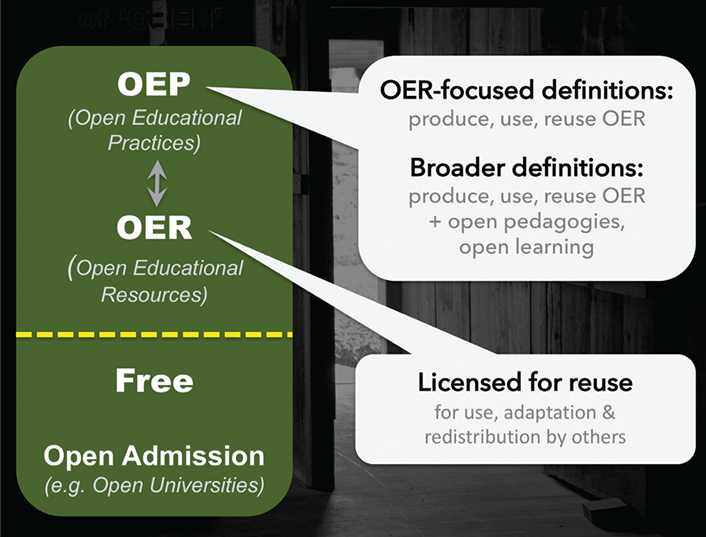

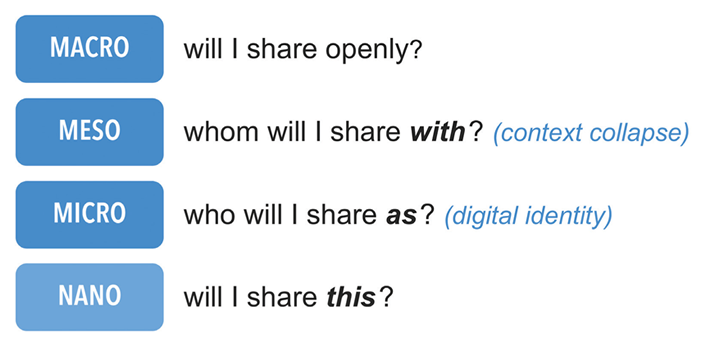

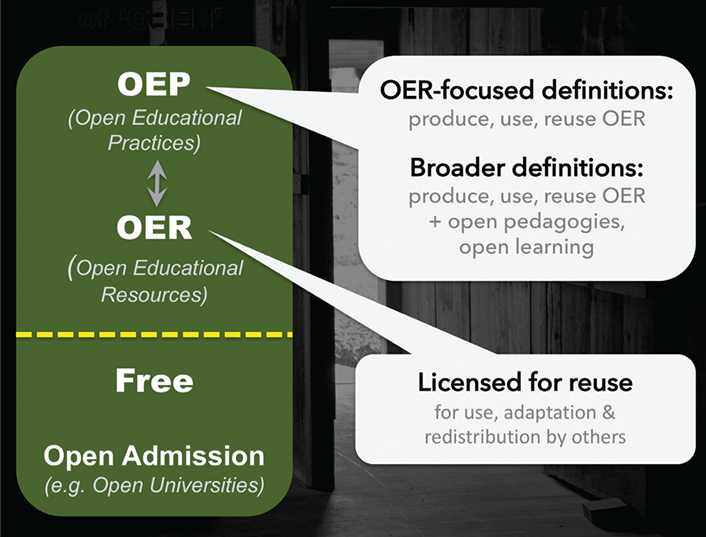

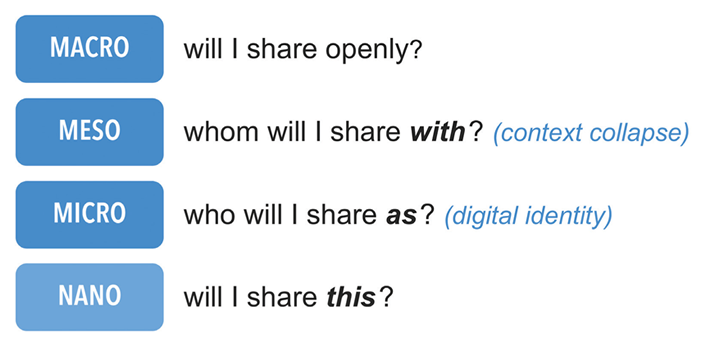

10. Open Education

11. Learning Analytics

12. Adaptive Teaching and Learning

13. Working with Emerging Technology

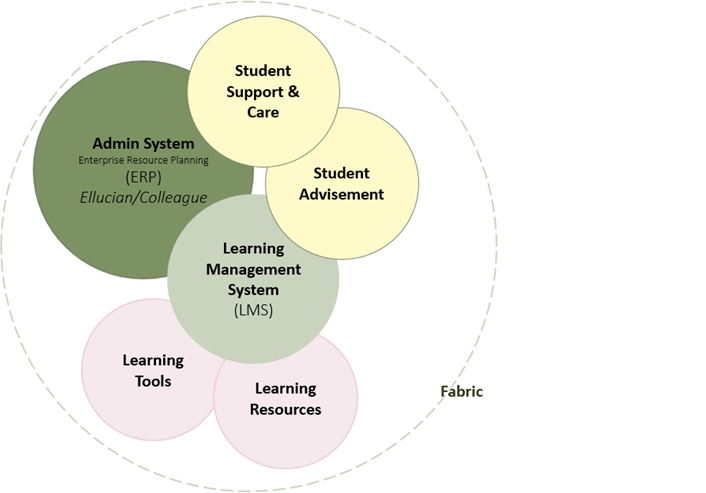

In 2014, administrators at Central Piedmont Community College (CPCC) in Charlotte, North Carolina, began talks with members of the North Carolina State Board of Community Colleges and North Carolina Community College System (NCCCS) leadership about starting a CBE program.

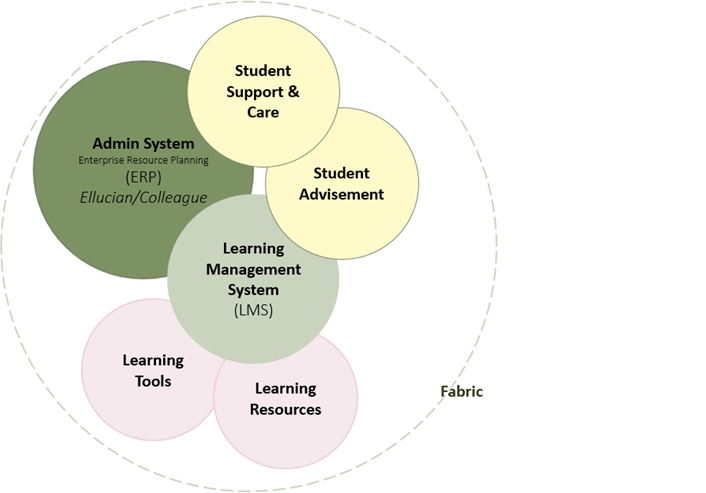

Building on an existing project at CPCC for identifying the elements of a digital learning environment (DLE), which was itself influenced by the EDUCAUSE publication The Next Generation Digital Learning Environment: A Report on Research,1 the committee reached consensus on a DLE concept and a shared lexicon: the “Digital Learning Environment Operational Definitions,