Building a Learning Innovation Network

https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/blogs/technology-and-learning/building-learning-innovation-network

a new interdisciplinary field of learning innovation emerging.

Learning innovation, as conceptualized as an interdisciplinary field, attempts to claim a space at the intersection of design, technology, learning science and analytics — all in the unique context of higher education.

professional associations, such as POD, ELI, UPCEA, (https://upcea.edu/) OLC (https://onlinelearningconsortium.org/), ASU GSV (https://www.asugsvsummit.com/) and SXSW Edu (https://www.sxswedu.com/) — among many other conferences and events put on by professional associations.

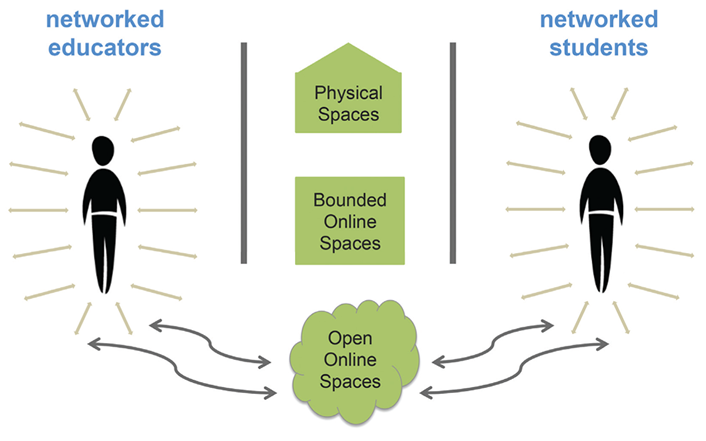

A professional community of practice differs from that of an interdisciplinary academic network. Professional communities of practice are connected through shared professional goals. Where best practices and shared experiences form the basis of membership in professional associations, academic networks are situated within marketplaces for ideas. Academic networks run on the generation of new ideas and scholarly exchange. These two network models are different.

+++++++++++

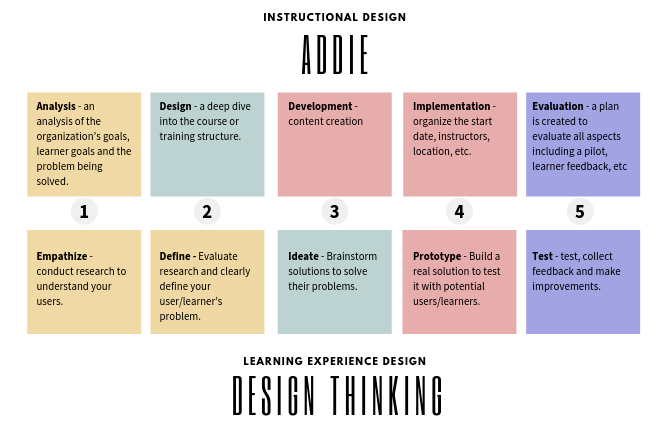

https://elearningindustry.com/learning-experience-design-instructional-design-difference

“Learning Experience Design™ is a synthesis of Instructional Design, educational pedagogy, neuroscience, social sciences, design thinking, and User Experience Design.”

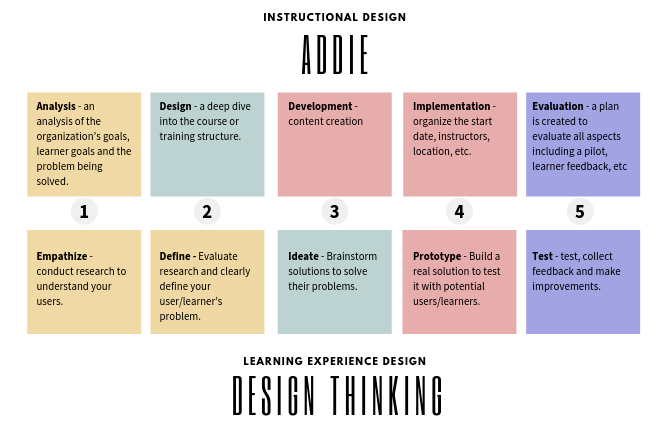

The Process: ADDIE Vs. Design Thinking

++++++++++++++

more on LX design in this iMS blog

https://blog.stcloudstate.edu/ims?s=learning+design

Emerging Technologies for Lifelong Learning:

Intro to #EmTechMOOC and EmTechWIKI from SUNY

“… open-access resource… to identify the value and implications of using established and emerging technology tools for personal and professional growth…strategies to … keep pace with technology change.

“… #EmTechMOOC, – Coursera Massive Open Online Course

“…EmTechWIKI …socially-curated discovery engine to discover tools, tutorials, and resources. The WIKI can be used as a stand-alone resource, or it can be used together with #EmTechMOOC. Anyone is welcome to add or edit WIKI resources.”

” – excerpt from https://www.coursera.org/learn/emerging-technologies-lifelong-learning,

Guests

Roberta (Robin) Sullivan, Online Learning Specialist, Center for Educational Innovation, University at Buffalo

Key Issues in Teaching and Learning

https://www.educause.edu/eli/initiatives/key-issues-in-teaching-and-learning

A roster of results since 2011 is here.

1. Academic Transformation

2. Accessibility and UDL

3. Faculty Development

4. Privacy and Security

5. Digital and Information Literacies

https://cdn.nmc.org/media/2017-nmc-strategic-brief-digital-literacy-in-higher-education-II.pdf

Three Models of Digital Literacy: Universal, Creative, Literacy Across Disciplines

United States digital literacy frameworks tend to focus on educational policy details and personal empowerment, the latter encouraging learners to become more effective students, better creators, smarter information consumers, and more influential members of their community.

National policies are vitally important in European digital literacy work, unsurprising for a continent well populated with nation-states and struggling to redefine itself, while still trying to grow economies in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent financial pressures

African digital literacy is more business-oriented.

Middle Eastern nations offer yet another variation, with a strong focus on media literacy. As with other regions, this can be a response to countries with strong state influence or control over local media. It can also represent a drive to produce more locally-sourced content, as opposed to consuming material from abroad, which may elicit criticism of neocolonialism or religious challenges.

p. 14 Digital literacy for Humanities: What does it mean to be digitally literate in history, literature, or philosophy? Creativity in these disciplines often involves textuality, given the large role writing plays in them, as, for example, in the Folger Shakespeare Library’s instructor’s guide. In the digital realm, this can include web-based writing through social media, along with the creation of multimedia projects through posters, presentations, and video. Information literacy remains a key part of digital literacy in the humanities. The digital humanities movement has not seen much connection with digital literacy, unfortunately, but their alignment seems likely, given the turn toward using digital technologies to explore humanities questions. That development could then foster a spread of other technologies and approaches to the rest of the humanities, including mapping, data visualization, text mining, web-based digital archives, and “distant reading” (working with very large bodies of texts). The digital humanities’ emphasis on making projects may also increase

Digital Literacy for Business: Digital literacy in this world is focused on manipulation of data, from spreadsheets to more advanced modeling software, leading up to degrees in management information systems. Management classes unsurprisingly focus on how to organize people working on and with digital tools.

Digital Literacy for Computer Science: Naturally, coding appears as a central competency within this discipline. Other aspects of the digital world feature prominently, including hardware and network architecture. Some courses housed within the computer science discipline offer a deeper examination of the impact of computing on society and politics, along with how to use digital tools. Media production plays a minor role here, beyond publications (posters, videos), as many institutions assign multimedia to other departments. Looking forward to a future when automation has become both more widespread and powerful, developing artificial intelligence projects will potentially play a role in computer science literacy.

6. Integrated Planning and Advising Systems for Student Success (iPASS)

7. Instructional Design

8. Online and Blended Learning

In traditional instruction, students’ first contact with new ideas happens in class, usually through direct instruction from the professor; after exposure to the basics, students are turned out of the classroom to tackle the most difficult tasks in learning — those that involve application, analysis, synthesis, and creativity — in their individual spaces. Flipped learning reverses this, by moving first contact with new concepts to the individual space and using the newly-expanded time in class for students to pursue difficult, higher-level tasks together, with the instructor as a guide.

Let’s take a look at some of the myths about flipped learning and try to find the facts.

Myth: Flipped learning is predicated on recording videos for students to watch before class.

Fact: Flipped learning does not require video. Although many real-life implementations of flipped learning use video, there’s nothing that says video must be used. In fact, one of the earliest instances of flipped learning — Eric Mazur’s peer instruction concept, used in Harvard physics classes — uses no video but rather an online text outfitted with social annotation software. And one of the most successful public instances of flipped learning, an edX course on numerical methods designed by Lorena Barba of George Washington University, uses precisely one video. Video is simply not necessary for flipped learning, and many alternatives to video can lead to effective flipped learning environments [http://rtalbert.org/flipped-learning-without-video/].

Myth: Flipped learning replaces face-to-face teaching.

Fact: Flipped learning optimizes face-to-face teaching. Flipped learning may (but does not always) replace lectures in class, but this is not to say that it replaces teaching. Teaching and “telling” are not the same thing.

Myth: Flipped learning has no evidence to back up its effectiveness.

Fact: Flipped learning research is growing at an exponential pace and has been since at least 2014. That research — 131 peer-reviewed articles in the first half of 2017 alone — includes results from primary, secondary, and postsecondary education in nearly every discipline, most showing significant improvements in student learning, motivation, and critical thinking skills.

Myth: Flipped learning is a fad.

Fact: Flipped learning has been with us in the form defined here for nearly 20 years.

Myth: People have been doing flipped learning for centuries.

Fact: Flipped learning is not just a rebranding of old techniques. The basic concept of students doing individually active work to encounter new ideas that are then built upon in class is almost as old as the university itself. So flipped learning is, in a real sense, a modern means of returning higher education to its roots. Even so, flipped learning is different from these time-honored techniques.

Myth: Students and professors prefer lecture over flipped learning.

Fact: Students and professors embrace flipped learning once they understand the benefits. It’s true that professors often enjoy their lectures, and students often enjoy being lectured to. But the question is not who “enjoys” what, but rather what helps students learn the best.They know what the research says about the effectiveness of active learning

Assertion: Flipped learning provides a platform for implementing active learning in a way that works powerfully for students.

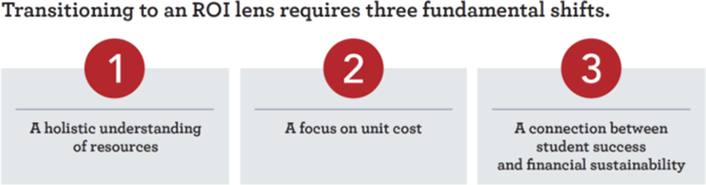

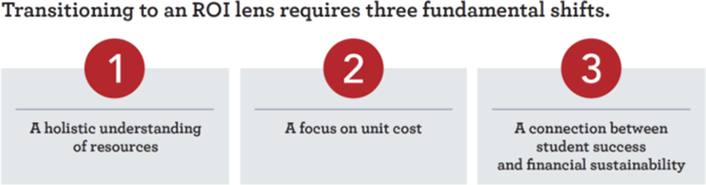

9. Evaluating Technology-based Instructional Innovations

What is the total cost of my innovation, including both new spending and the use of existing resources?

What’s the unit I should measure that connects cost with a change in performance?

How might the expected change in student performance also support a more sustainable financial model?

The Exposure Approach: we don’t provide a way for participants to determine if they learned anything new or now have the confidence or competence to apply what they learned.

The Exemplar Approach: from ‘show and tell’ for adults to show, tell, do and learn.

The Tutorial Approach: Getting a group that can meet at the same time and place can be challenging. That is why many faculty report a preference for self-paced professional development.build in simple self-assessment checks. We can add prompts that invite people to engage in some sort of follow up activity with a colleague. We can also add an elective option for faculty in a tutorial to actually create or do something with what they learned and then submit it for direct or narrative feedback.

The Course Approach: a non-credit format, these have the benefits of a more structured and lengthy learning experience, even if they are just three to five-week short courses that meet online or in-person once every week or two.involve badges, portfolios, peer assessment, self-assessment, or one-on-one feedback from a facilitator

The Academy Approach: like the course approach, is one that tends to be a deeper and more extended experience. People might gather in a cohort over a year or longer.Assessment through coaching and mentoring, the use of portfolios, peer feedback and much more can be easily incorporated to add a rich assessment element to such longer-term professional development programs.

The Mentoring Approach: The mentors often don’t set specific learning goals with the mentee. Instead, it is often a set of structured meetings, but also someone to whom mentees can turn with questions and tips along the way.

The Coaching Approach: A mentor tends to be a broader type of relationship with a person.A coaching relationship tends to be more focused upon specific goals, tasks or outcomes.

The Peer Approach:This can be done on a 1:1 basis or in small groups, where those who are teaching the same courses are able to compare notes on curricula and teaching models. They might give each other feedback on how to teach certain concepts, how to write syllabi, how to handle certain teaching and learning challenges, and much more. Faculty might sit in on each other’s courses, observe, and give feedback afterward.

The Self-Directed Approach:a self-assessment strategy such as setting goals and creating simple checklists and rubrics to monitor our progress. Or, we invite feedback from colleagues, often in a narrative and/or informal format. We might also create a portfolio of our work, or engage in some sort of learning journal that documents our thoughts, experiments, experiences, and learning along the way.

The Buffet Approach:

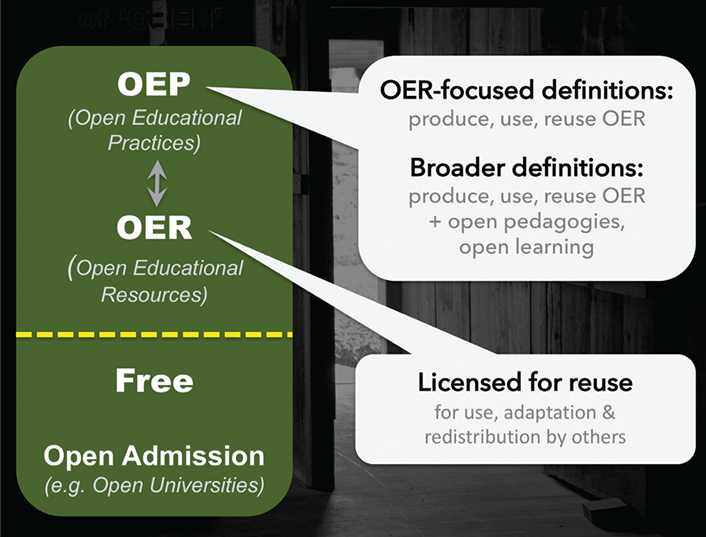

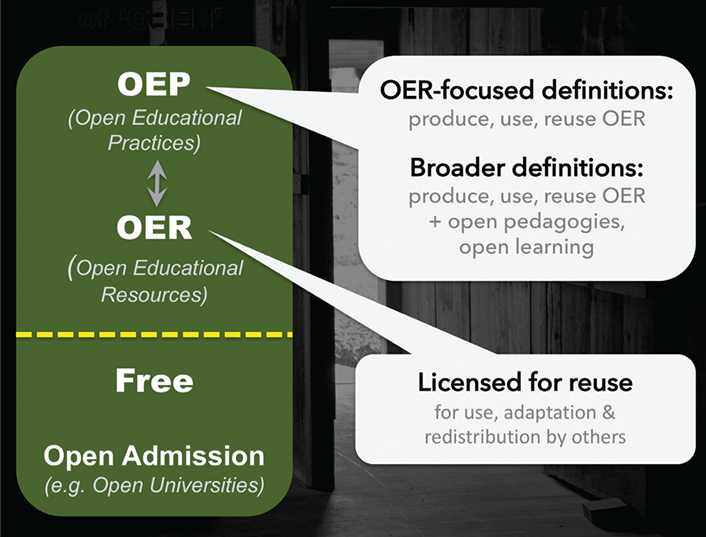

10. Open Education

11. Learning Analytics

12. Adaptive Teaching and Learning

13. Working with Emerging Technology

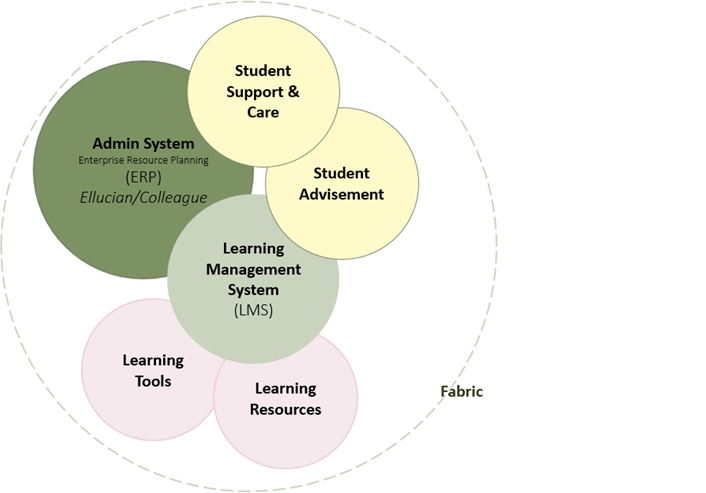

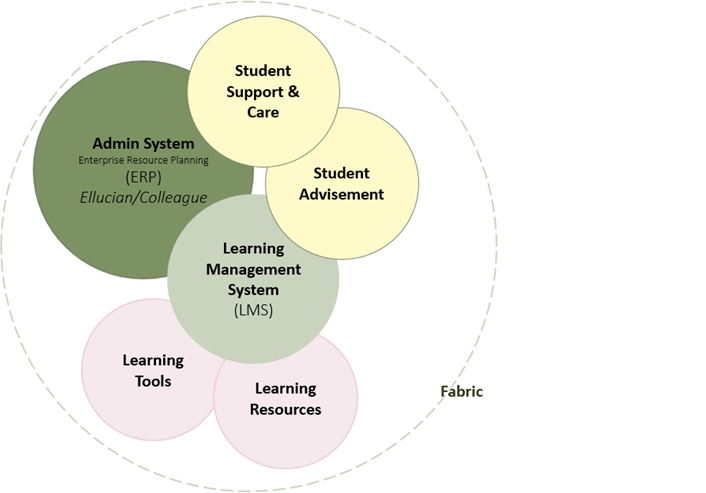

In 2014, administrators at Central Piedmont Community College (CPCC) in Charlotte, North Carolina, began talks with members of the North Carolina State Board of Community Colleges and North Carolina Community College System (NCCCS) leadership about starting a CBE program.

Building on an existing project at CPCC for identifying the elements of a digital learning environment (DLE), which was itself influenced by the EDUCAUSE publication The Next Generation Digital Learning Environment: A Report on Research,1 the committee reached consensus on a DLE concept and a shared lexicon: the “Digital Learning Environment Operational Definitions,

How to Craft Useful, Student-Centered Social Media Policies

By Tanner Higgin  08/09/18

08/09/18

https://thejournal.com/articles/2018/08/09/how-to-craft-useful-student-centered-social-media-policies.aspx

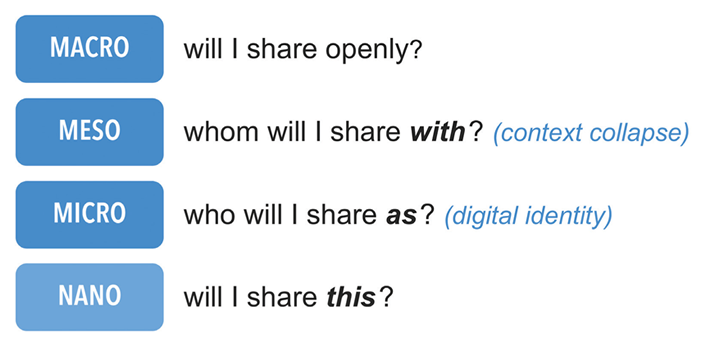

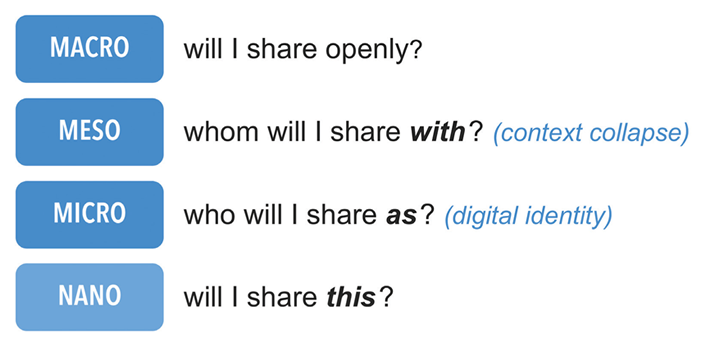

Whether your school or district has officially adopted social media or not, conversations are happening in and around your school on everything from Facebook to Snapchat. Schools must reckon with this reality and commit to supporting thoughtful and critical social media use among students, teachers and administrators. If not, schools and classrooms risk everything from digital distraction to privacy violations.

Key Elements to Include in a Social Media Policy

- Create parent opt-out forms that specifically address social media use.Avoid blanket opt-outs that generalize all technology or obfuscate how specific social media platforms will be used. (See this example by the World Privacy Forum as a starting point.)

- Use these opt-out forms as a way to have more substantive conversations with parents about what you’re doing and why.

- Describe what platforms are being used, where, when and how.

- Avoid making the consequences of opt-out selections punitive (e.g., student participation in sports, theater, yearbook, etc.).

- Establish baseline guidelines for protecting and respecting student privacy.

- Prohibit the sharing of student faces.

- Restrict location sharing: Train teachers and students on how to turn off geolocation features/location services on devices as well as in specific apps.

- Minimize information shared in teacher’s social media profiles: Advise teachers to list only grade level and subject in their public profiles and not to include specific school or district information.

- Make social media use transparent to students: Have teachers explain their social media plan, and find out how students feel about it.

- Most important: As with any technology, attach social media use to clearly articulated goals for student learning. Emphasize in your guidelines that teachers should audit any potential use of social media in terms of student-centered pedagogy: (1) Does it forward student learning in a way impossible through other means? and (2) Is using social media in my best interests or in my students’?

Moving from Policy to Practice.

Social media policies, like policies in general, are meant to mitigate the risk and liability of institutions rather than guide and support sound pedagogy and student learning. They serve a valuable purpose, but not one that impacts classrooms. So how do we make these policies more relevant to classrooms?

First, it forces policy to get distilled into what impacts classroom instruction and administration. Second, social media changes monthly, and it’s much easier to update a faculty handbook than a policy document. Third, it allows you to align social media issues with other aspects of teaching (assessment, parent communication, etc.) versus separating it out in its own section.

++++++++++

more on social media in education in this IMS blog

https://blog.stcloudstate.edu/ims?s=social+media+education

more on social media policies in this IMS blog

https://blog.stcloudstate.edu/ims?s=social+media+policies

Student Perceptions of Learning and Instructional Effectiveness in College Courses

https://www.ets.org/Media/Products/perceptions.pdf

Students’ Perception of Gamification in Learning and Education.

https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007%2F978-3-319-47283-6_6

College students’ perceptions of pleasure in learning – Designing gameful gamification in education

investigate behavioral and psychological metrics that could affect learner perceptions of technology

today’s learners spend extensive time and effort posting and commenting in social media and playing video games

Creating pleasurable learning experiences for learners can improve learner engagement.

uses game-design elements in non-gaming environments with the purpose of motivating users to behave in a certain direction (Deterding et al., 2011)

How can we facilitate the gamefulness of gamification?

Most gamified activities include three basic parts: “goal-focused activity, reward mechanisms, and progress tracking” (Glover, 2013, p. 2000).

gamification works similarly to the instructional methods in education – clear learning and teaching objectives, meaningful learning activities, and assessment methods that are aligned with the objectives

the design of seven game elements:

- Storytelling: It provides the rules of the gamified activities. A good gamified activity should have a clear and simple storyboard to direct learners to achieve the goals. This game-design element works like the guidelines and directions of an instructional activity in class.

- Levels: A gamified activity usually consists of different levels for learners to advance through. At each level, learners will face different challenges. These levels and challenges can be viewed as the specific learning objectives/competencies for learners to accomplish.

- Points: Points pertain to the progress-tracking element because learners can gain points when they complete the quests.

- Leaderboard: This element provides a reward mechanism that shows which learners are leading in the gamified activities. This element is very controversial when gamification is used in educational contexts because some empirical evidence shows that a leaderboard is effective only for users who are aggressive and hardcore players (Hamari, Koivisto, & Sarsa, 2014).

- Badges: These serve as milestones to resemble the rewards that learners have achieved when they complete certain quests. This element works as the extrinsic motivation for learners (Kapp, 2012).

- Feedback: A well-designed gamification interface should provide learners with timely feedback in order to help them to stay on the right track.

- Progress: A progress-tracking bar should appear in the learner profile to remind learners of how many quests remain and how many quests they have completed.

Dominguez et al. (2013) suggested that gamification fosters high-order thinking, such as problem-solving skills, rather than factual knowledge. Critical thinking, which is commonly assessed in social science majors, is also a form of higher-order thinking.

Davis (1989) developed technology acceptance model (TAM) to help people understand how users perceive technologies. Pleasure, arousal, and dominance (PAD) emotional-state model that developed by Mehrabian (1995) is one of the fundamental design frameworks for scale development in understanding user perceptions of user-system interactions.

Van der Heijdedn (2004) asserted that pleasurable experiences encouraged users to use the system for a longer period of time

Self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 1985) has been integrated into the design of gamification and addressed the balance between learners’ extrinsic and intrinsic motivation.

Ryan and Deci (2000) concluded that extrinsic rewards might suppress learners’ intrinsic motivation. Exploiting the playfulness and gamefulness in gamification, therefore, becomes extremely important, as it would employ the most effective approaches to engage learners.

Sweetser and Wyeth (2005) developed GameFlow as an evaluation model to measure player enjoyment in games

Fu, Su, and Yu (2009) adapted this scale to EGameFlow in order to measure college students’ enjoyment of e-learning games. EGameFlow is a multidimensional scale that consists of self-evaluated emotions.

Eppmann, Bekk, and Klein (2018) developed gameful experience scale (GAMEX) to measure gameful experiences for gamification contexts. one of the limitations of GAMEX to be used in education is that its effects on learning outcome has not been studied

the Big Five Model, which has been proposed as trait theory by McCrae & Costa (1989) and is widely accepted in the field, to measure the linkages between the game mechanics in gamification and the influences of different personality traits.

Storytelling in the subscale of Preferences for Instruction emphasizes the rules of the gamified learning environments, such as the syllabus of the course, the rubrics for the assignments, and the directions for tasks. Storytelling in the subscale of Preferences for Instructors’ Teaching Style focuses on the ways in which instructors present the content. For example, instructors could use multimedia resources to present their instructional materials. Storytelling in the subscale of Preferences for Learning Effectiveness emphasizes scaffolding materials for the learners, such as providing background information for newly introduced topics.

The effective use of badges would include three main elements: signifier, completion logic, and rewards (Hamari & Eranti, 2011). A useful badge needs clear goal-setting and prompt feedback. Therefore, badges correlate closely with the design of storytelling (rules) and feedback, which are the key game design elements in the subscale of Preferences for Instruction.

Students can use Google to search on their laptops or tablets in class when instructors introduce new concepts. By reading the reviews and viewing the numbers of “thumbs-up” (agreements by other users), students are able to select the best answers. Today’s learners also “tweet” on social media to share educational videos and news with their classmates and instructors. Well-designed gamified learning environments could increase pleasure in learning by allowing students to use familiar computing experiences in learning environments.

Rethinking Social Media to Organize Information and Communities eCourse

Tired of hearing all the reasons why you should be using Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, and other popular social media tools? Perhaps it’s time to explore social media tools in a supportive and engaging environment with a keen eye toward using those tools more effectively in your work.

Join us and social media guru and innovator Paul Signorelli in this four-week, highly-interactive eCourse as he explores a variety of social media tools in terms of how they can be used to organize information and communities. Together, you will survey and use a variety of social media tools, such as Delicious, Diigo, Facebook, Goodreads, Google Hangouts, LibraryThing, Pinterest, Twitter, and more! You will also explore how social media tools can be used to organize and disseminate information and how they can be used to foster and sustain communities of learning.

After participating in this eCourse, you will have an:

- Awareness of how social media tools can be used to support the work you do with colleagues and other community stakeholders in fostering engagement through onsite and online communities

- Increased ability to identify, explore, and foster the use of social media tools that support you and those you serve

- Increased ability to use a variety of social media tools effectively in your day-to-day work

Part 1: Using Social Media Tools to Organize and Provide Access to Information

Delicious, Diigo, Goodreads, LibraryThing, and other tagging sites

Part 2: Organizing, Marketing, and Running Programs

Facebook, Pinterest, and other tools for engagement

Part 3: Expanding and Analyzing Community Impact

Twitter, Storify, and other microblogging resources

Part 4: Sustaining Engagement with Community Partners

Coordinating your presence and interactions across a variety of social media tools

trainer-instructional designer-presenter-consultant. Much of his work involves fostering community and collaboration face-to-face and online through libraries, other learning organizations, and large-scale community-based projects including San Francisco’s Hidden Garden Steps project, which has its origins in a conversation that took place within a local branch library. He remains active on New Media Consortium Horizon Report advisory boards/expert panels, in the Association for Talent Development (ATD–formerly the American Society for Training & Development), and with the American Library Association; adores blended learning; and remains a firm advocate of developing sustainable onsite and online community partnerships that meet all partners’ needs. He is co-author of Workplace Learning & Leadership with Lori Reed and author of the upcoming Change the World Using Social Media (Rowman & Littlefield, Autumn 2018).

++++++++++++

more on social media in libraries

https://blog.stcloudstate.edu/ims?s=social+media+library

How to Craft Useful, Student-Centered Social Media Policies

08/09/18 Tanner Higgin

https://thejournal.com/articles/2018/08/09/how-to-craft-useful-student-centered-social-media-policies.aspx

Whether your school or district has officially adopted social media or not, conversations are happening in and around your school on everything from Facebook to Snapchat.

Use policy creation as an opportunity to take inventory of your students’ needs, how social media is already being used by your teachers, and how policy can support both responsibly.

1. Create parent opt-out forms that specifically address social media use.

2. Establish baseline guidelines for protecting and respecting student privacy.

3. Make social media use transparent to students

4. Most important: As with any technology, attach social media use to clearly articulated goals for student learning

Moving from Policy to Practice

Social media isn’t a novel phenomenon requiring separate attention. Ed tech, and the tech world in general, wants to tout every new development as a revolution. Most, however, are an iteration. While we get caught up re-inventing everything to wrestle with a perceived social media sea change, our students see it simply as a part of school life.

++++++++++++

more on social media in education in this IMS blog

https://blog.stcloudstate.edu/ims?s=social+media+education

08/09/18

08/09/18