Compensation for creation of online courses

++++++++++++++++++++

I absolutely echo Kimber’s notion that a team approach to course development can actually take longer, even when one of the team members is an instructional designer. Perhaps because faculty members are used to controlling all aspects of their course development and delivery, the division of labor concept may feel too foreign to them. An issue that is similar in nature and referred to as ‘unbundling the faculty role’ is discussed at length in the development of competency-based education (CBE) courses and it is not typically a concept that faculty embrace.

Robin

+++++++++++++++++++

I will also confirm that the team approach to course development can take longer. Indeed it does in my experience. It requires much more “back and forth”, negotiating of who is doing what, ensuring that the overall approach is congruent, etc. That’s not to say that it’s not a worthwhile endeavor in some cases where it makes pedagogical sense (in our case we are designing courses for 18-22 year-old campus-based learners and 22+ year-old fully online learners at the same time), but if time/cost savings is the goal, you will be sorely disappointed, in my experience. The “divide and conquer” approach requires a LOT of coordination and oversight. Without that you will likely have a cobbled together, hodgepodge of a course that doesn’t meet expectations.

Best, Carine Director, Office of Instructional Design & Academic Technology Ottawa University 1001 S. Cedar St. * Ottawa, KS 66067 carine.ullom@ottawa.edu * 785-248-2510

++++++++++++++++++++

Breaking up a course and coming up with a cohesive design and approach, could make the design process longer. At SSC, we generally work with our faculty over the course of a semester for each course. When we’ve worked with teams, we have not seen a shortened timeline.

The length of time it takes to develop a course depends on the content. Are there videos? If so, they have to be created, which is time-consuming, plus they either need to have a transcript created or they need subtitles. Both of those can be time-consuming. PowerPoint slides take time, plus, they need more content to make them relevant. We are working with our faculty to use the Universal Design for Learning model, which means we’re challenging them to create the content to benefit the most learners

I have a very small team whose sole focus is course design and it takes us 3-4 weeks to design a course and it’s our full-time job!

Linda

Linda C. Morosko, MA Director, eStarkState Division of Student Success 330-494-6170 ext. 4973 lmorosko@starkstate.edu

+++++++++++++++++++++++++

Kelvin, we also use the 8-week development cycle, but do occasionally have to lengthen that cycle for particularly complex courses or in rare cases when the SME has had medical emergencies or other major life disruptions. I would be surprised if multiple faculty working on a course could develop it any more quickly than a single faculty member, though, because of the additional time required for them to agree and the dispersed sense of responsibility. Interesting idea.

-Kimber

Dr. Kimberly D. Barnett Gibson, Assistant Vice President for Academic Affairs and Online Learning Our Lady of the Lake University 411 SW 24th Street San Antonio, TX 78207 Kgibson@ollusa.edu 210.431.5574 BlackBoard IM kimberly.gibson https://www.pinterest.com/drkdbgavpol/ @drkimberTweets

++++++++++++++++++++++++

Hello everyone. As a follow-up to the current thread, how long do you typically give hey course developer to develop a master course for your institution? We currently use an eight week model but some faculty have indicated that that is not enough time for them although we have teams of 2 to 4 faculty developing such content. Our current assumption is that with teams, there can be divisions of labor that can reduce the total amount time needed during the course development process.

Kelvin Bentley, PhD Vice President of Academic Affairs, TCC Connect Campus Tarrant County College District

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++

At Berkeley College, full-time faculty may develop online courses in conjunction with an instructional designer. The course is used as a master template for other sections to be assigned from. Once the course has been scheduled and taught, the faculty member receives a stipend. The faculty member would receive their normal pay to teach the developed course as part of their semester course load, with no additional royalties assigned for it or any additional sections that may be provided to students.

Regards, Gina Gina Okun Assistant Dean, Online Berkeley College 64 East Midland Avenue, Suite 2, Paramus, NJ 07652 (973)405-2111 x6309 gina-okun@berkeleycollege.edu

+++++++++++++++++++++++++

We operate with nearly all adjunct faculty where >70% of enrollment credits are onlinez

With one exception that I can recall, the development contract includes the college’s outright ownership, with no royalty rights. One of the issues with a royalty based arrangement would be what to do when the course is revised (which happens nearly every term, to one degree or another). At what point does the course begin to take on the character of another person’s input?

What do you do if the course is adapted for a shorter summer term, or a between-term intensive? What if new media tools or a different LMS are used? Is the royalty arrangement based on the syllabus or the course content itself? What happens if the textbook goes out of print, or an Open resource becomes available? What happens if students evaluate the course poorly?

I’m not in position to set this policy — I’m only reporting it. I like the idea of a royalty arrangement but it seems like it could get pretty messy. It isn’t as if you are licensing a song or an image where the original product doesn’t change. Courses, the modes of delivery, and the means of communication change all the time. Seems like it would be hard to define what constitutes “the course” after a certain amount of time.

Steve Covello Rich Media Specialist/Instructional Designer/Online Instructor Chalk & Wire e-Portfolio Administrator Granite State College 603-513-1346 Video chat: https://appear.in/id.team Scheduling: http://meetme.so/stevecovello

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

I’ve worked with many institutions that have used Subject Matter Experts (SMEs) to develop or provide the online course content. Most often, the institutions also provide a resource in the form of an Instructional Designer (ID) to take the content and create the actual course environment.

The SME is paid on a contract basis for provision of the content. This is a one-time payment, and the institution then owns the course content (other than integrated published materials such as text books, licensed online lab products, etc.). The SME may be an existing faculty member at the institution or not, or the SME may go on to teach the course at the institution. In any event, whoever teaches the course would be paid the standard faculty rate for the course. If the course requires revisions to the extent that a person will need to be engaged for content updates, then that can be a negotiated contract. Typically it is some fraction of the original development cost. No royalties are involved.

Hap Aziz, Ed.D. @digitalhap http:hapaziz.wordpress.com

++++++++++++++++++++

Within SUNY, there is some variance regarding whether a stipend is paid for development or not. In either case, since we are unionized there is policy regarding IP. IP resides with the faculty developer unless both parties agree in writing in the form of a contract to assign or share rights.

Policy statement: http://uupinfo.org/reports/reportpdf/IntellectualPropertyUpdated2016.pdf

Thank you for your feedback on this issue. Our institution does does not provide a royalty as we consider course development as a fee-for-service arrangement. We pay teams of 2-4 faculty $1000 each to develop master course shells for our high-enrollment courses. Instead of a royalty fee, I think an institution can simply provide course developers the perk of first right of refusal to teach the course when it offered as well as providing course developers with the first option to make revisions to the course shell over time.

Kelvin

Kelvin Bentley, Ph.D. Vice President of Academic Affairs, TCC Connect Campus Tarrant County College District

Once upon a time, and several positions ago, we set up a google doc for capturing all kinds of data points across institutions, like this. I’m sure it’s far out of date, but may still have some ideas or info in there – and could possibly be dusted off and oiled up for re-use… I present the Blend-Online Data Collector. This tab is for course development payment.

Kind regards,

Clark

Clark Shah-Nelson

Assistant Dean, Instructional Design and Technology

University of Maryland School of Social Work—Twitter … LinkedIn —voice/SMS: (646) 535-7272fax: 270.514.0112

Hi Jenn,

Just want to clarify…you say faculty “sign over all intellectual property rights of the course to the college.” but later in the email say “Faculty own all intellectual property and can take it with them to teach at another institution”, so is your policy changing to the former? Or, is it the later and that is what you are asking about?

I’ll send details on our policy directly to your email account.

Best,

Ellen

On Tue, Dec 6, 2016 at 9:43 AM, Jennifer Stevens <jennifer_stevens@emerson.edu> wrote:

Hello all,

I am tasked with finding out what the going rate is for the following model:

We pay an adjunct faculty member (“teaching faculty”) a set amount in order to develop an online course and sign over all intellectual property rights of the course to the college.

Is anyone doing this? I’ve heard of models that include royalties, but I personally don’t know of any that offer straight payment for IP. I know this can be a touchy subject, so feel free to respond directly to me and I will return and post a range of payment rates with no other identifying data.

For some comparison, we are currently paying full time faculty a $5000 stipend to spend a semester developing their very first online class, and then they get paid to teach the class. Subsequent online class developments are unpaid. Emerson owns the course description and course shell and is allowed to show the course to future faculty who will teach the online course. Faculty own all intellectual property and can take it with them to teach at another institution. More info: http://www.emerson.edu/itg/online-emerson/frequently-asked-questions

I asked this on another list, but wanted to get Blend_Online’s opinion as well. Thanks for any pointers!

Jenn Stevens

Director | Instructional Technology Group | 403A Walker Building | Emerson College | 120 Boylston St | Boston MA 02116 | (617) 824-3093

Ellen M. Murphy

Director of Program Development

Graduate Professional Studies

Brandeis University Rabb School

781-736-8737

++++++++++++++++

more on compensation for online courses in this IMS blog:

https://blog.stcloudstate.edu/ims?s=online+compensation

bibliography on “open access”

permanent link to the search: http://scsu.mn/2dtGtUg

Tomlin, P. (2009). A Matter of Discipline: Open Access, the Humanities, and Art History. Canadian Journal Of Higher Education, 39(3), 49-69.

Recent events suggest that open access has gained new momentum in the humanities, but the slow and uneven development of open-access initiatives in humanist fields continues to hinder the consolidation of efforts across the university. Although various studies have traced the general origins of the humanities’ reticence to embrace open access, few have actually considered the scholarly practices and disciplinary priorities that shape a discipline’s adoption of its principles. This article examines the emergence, potential and actualized, of open access in art history. Part case study, part conceptual mapping, the discussion is framed within the context of three interlocking dynamics: the present state of academic publishing in art history; the dominance of the journal and self-archiving repository within open-access models of scholarly production; and the unique roles played by copyright and permissions in art historical scholarship. It is hoped that tracing the discipline-specific configuration of research provides a first step toward both investigating the identity that open access might assume within the humanities, from discipline to discipline, and explaining how and why it might allow scholars to better serve themselves and their audiences.

Solomon, D. J., & Björk, B. (2012). A study of open access journals using article processing charges. Journal Of The American Society For Information Science & Technology, 63(8), 1485-1495. doi:10.1002/asi.22673

Article processing charges ( APCs) are a central mechanism for funding open access (OA) scholarly publishing. We studied the APCs charged and article volumes of journals that were listed in the Directory of Open Access Journals as charging APCs. These included 1,370 journals that published 100,697 articles in 2010. The average APC was $906 U.S. dollars (USD) calculated over journals and $904 USD calculated over articles. The price range varied between $8 and $3,900 USD, with the lowest prices charged by journals published in developing countries and the highest by journals with high-impact factors from major international publishers. Journals in biomedicine represent 59% of the sample and 58% of the total article volume. They also had the highest APCs of any discipline. Professionally published journals, both for profit and nonprofit, had substantially higher APCs than journals published by societies, universities, or scholars/researchers. These price estimates are lower than some previous studies of OA publishing and much lower than is generally charged by subscription publishers making individual articles OA in what are termed hybrid journals.

Beaubien, S., & Eckard, M. (2014). Addressing Faculty Publishing Concerns with Open Access Journal Quality Indicators. Journal Of Librarianship & Scholarly Communication, 2(2), 1-11. doi:10.7710/2162-3309.1133

BACKGROUND The scholarly publishing paradigm is evolving to embrace innovative open access publication models. While this environment fosters the creation of high-quality, peer-reviewed open access publications, it also provides opportunities for journals or publishers to engage in unprofessional or unethical practices. LITERATURE REVIEW Faculty take into account a number of factors in deciding where to publish, including whether or not a journal engages in ethical publishing practices. Librarians and scholars have attempted to address this issue in a number of ways, such as generating lists of ethical/unethical publishers and general guides. DESCRIPTION OF PROJECT In response to growing faculty concern in this area, the Grand Valley State University Libraries developed and evaluated a set of Open Access Journal Quality Indicators that support faculty in their effort to identify the characteristics of ethical and unethical open access publications. NEXT STEPS Liaison librarians have already begun using the Indicators as a catalyst in sparking conversation around open access publishing and scholarship. Going forward, the Libraries will continue to evaluate and gather feedback on the Indicators, taking into account emerging trends and practices.

Husain, S., & Nazim, M. (2013). Analysis of Open Access Scholarly Journals in Media & Communication. DESIDOC Journal Of Library & Information Technology, 33(5), 405-411.

he paper gives an account of the origin and development of the Open Access Initiative and explains the concept of open access publishing. It also highlight various facets related to the open access scholarly publishing in the field of Media & Communication on the basis of data collected from the most authoritative online directory of open access journals, i.e., Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ). The DOAJ covers 8492 open access journals of which 106 journals are listed under the subject heading ‘Media & Communication’. Most of the open access journals in Media & Communication were started during late 1990s and are being published from 34 different countries on 6 continents in 13 different languages. More than 80 % open access journals are being published by the not-for-profit sector such as academic institutions and universities.

Reed, K. (2014). Awareness of Open Access Issues Differs among Faculty at Institutions of Different Sizes. Evidence Based Library & Information Practice, 9(4), 76-77.

Objective — This study surveyed faculty awareness of open access (OA) issues and the institutional repository (IR) at the University of Wisconsin. The authors hoped to use findings to inform future IR marketing strategies to faculty. Design — Survey. Setting — University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire, a small, regional public university (approximately 10,000 students). Subjects — 105 faculty members. Methods — The authors contacted 397 faculty members inviting them to participate in an 11 question online survey. Due to anonymity issues on a small campus, respondents were not asked about rank and discipline, and were asked to not provide identifying information. A definition of OA was not provided by the authors, as survey participants were queried about their own definition. Main Results — Approximately 30% of the faculty were aware of OA issues. Of all the definitions of OA given by survey respondents, “none … came close” to the definition favoured by the authors (p. 145). More than 30% of the faculty were unable to define OA at a level deemed basic by the authors. A total of 51 (48.57%) of the survey respondents indicated that there are OA journals in their disciplines. Another 6 (5.71%) of the faculty members claimed that there are no OA journals in their disciplines, although most provided a definition of OA and several considered OA publishing to be “very important.” The remaining 48 participants (46%) were unsure if there are OA journals in their disciplines. Of these survey respondents, 38 answered that they have not published in an OA journal, 10 were unsure, and 21 believed that their field benefits or would benefit from OA journals. Survey respondents cited quality of the journal, prestige, and peer review as extremely important in selecting a journal in which to publish. Conclusion — The authors conclude that the level of awareness related to OA issues must be raised before IRs can flourish. They ponder how university and college administrators regard OA publishing, and the influence this has on the tenure and promotion process

KELTY, C. (2014). BEYOND COPYRIGHT AND TECHNOLOGY: What Open Access Can Tell Us about Precarity, Authority, Innovation, and Automation in the University Today. Cultural Anthropology (Society For Cultural Anthropology), 29(2), 203-215. doi:10.14506/ca29.2.02

In this interview, we discuss what open access can teach us about the state of the university, as well as practices in scholarly publishing. In particular the focus is on issues of labor and precarity, the question of how open access enables or blocks other innovations in scholarship, the way open access might be changing practices of scholarship, and the role of technology and automation in the creation, evaluation, and circulation of scholarly work

Armbruster, C. (2008). Cyberscience and the Knowledge-Based Economy. Open Access and Trade Publishing: From Contradiction to Compatibility with Non-Exclusive Copyright Licensing. Policy Futures In Education, 6(4), 439-452.

Open source, open content and open access are set to fundamentally alter the conditions of knowledge production and distribution. Open source, open content and open access are also the most tangible result of the shift towards e-science and digital networking. Yet, widespread misperceptions exist about the impact of this shift on knowledge distribution and scientific publishing. It is argued, on the one hand, that for the academy there principally is no digital dilemma surrounding copyright and there is no contradiction between open science and the knowledge-based economy if profits are made from non-exclusive rights. On the other hand, pressure for the “digital doubling” of research articles in open access repositories (the “green road”) is misguided and the current model of open access publishing (the “gold road”) has not much future outside biomedicine. Commercial publishers must understand that business models based on the transfer of copyright have not much future either. Digital technology and its economics favour the severance of distribution from certification. What is required of universities and governments, scholars and publishers, is to clear the way for digital innovations in knowledge distribution and scholarly publishing by enabling the emergence of a competitive market that is based on non-exclusive rights. This requires no change in the law but merely an end to the praxis of copyright transfer and exclusive licensing. The best way forward for research organisations, universities and scientists is the adoption of standard copyright licences that reserve some rights, namely Attribution and No Derivative Works, but otherwise will allow for the unlimited reproduction, dissemination and re-use of the research article, commercial uses included.

Kuth, M. (2012). ‘Deswegen wird kein Buch weniger verkauft!’ Hybride Publikation von MALIS Praxisprojekten an der Fachhochschule Köln. (German). Bibliothek Forschung Und Praxis, 36(1), 103-109.

The article reports on a library and information science project at the Fachhochschule Köln (University of Applied Sciences, Cologne), Germany, to produce a hybrid, print and online research publication, “MALIS Praxisprojekte 2011,” which is available at http://www.b-i-t-online.de/daten/bitinnovativ.php#band35. It discusses the publishing process from writing to distribution and the implications of combining open access and for-fee publishing models for value chains in the publishing industry.

Riedel, S. (2012). Distanz zu Wissenschaftlern und Studenten verringern. (German). Bub: Forum Bibliothek Und Information, 64(7/8), 491-492.

A report from the International Bielefeld Conference on April 24-26, 2012 in Bielefeld, Germany is presented. Presentations discussed include the role of information storage and retrieval in libraries, Open Access publishing and content licenses, and the increased automation of the Bielefeld University library.

Ramirez, M., Dalton, J. j., McMillan, G. g., Read, M., & Seamans, N.. (2013). Do Open Access Electronic Theses and Dissertations Diminish Publishing Opportunities in the Social Sciences and Humanities? Findings from a 2011 Survey of Academic Publishers. College & Research Libraries, 74(4), 368-380.

n increasing number of higher education institutions worldwide are requiring submission of electronic theses and dissertations (ETDs) by graduate students and are subsequently providing open access to these works in online repositories. Faculty advisors and graduate students are concerned that such unfettered access to their work could diminish future publishing opportunities. This study investigated social sciences, arts, and humanities journal editors’ and university press directors’ attitudes toward ETDs. The findings indicate that manuscripts that are revisions of openly accessible ETDs are always welcome for submission or considered on a case-by-case basis by 82.8 percent of journal editors and 53.7 percent of university press directors polled.

Schuurman, N. (2013). Editorial /Éditorial. Canadian Geographer, 57(2), 117-118. doi:10.1111/cag.12027

The author reflects on the use of the Open Access (OA) publishing for publications. She states that in OA publishing, an un-blinded peer review format is used wherein the authors’ names are known to the reviewer. She mentions that the countries such as Great Britain and Canada passed legislations which mandates the use of OA journals in university publications and health research. She also relates the impact of the changes in publishing to the print versions of journals.

Bazeley, J. W., Waller, J., & Resnis, E. (2014). Engaging Faculty in Scholarly Communication Change: A Learning Community Approach. Journal Of Librarianship & Scholarly Communication, 2(3), 1-13. doi:10.7710/2162-3309.1129

As the landscape of scholarly communication and open access continues to shift, it remains important for academic librarians to continue educating campus stakeholders about these issues, as well as to create faculty advocates on campus. DESCRIPTION OF PROGRAM Three librarians at Miami University created a Faculty Learning Community (FLC) on Scholarly Communication to accomplish this. The FLC, composed of faculty, graduate students, staff, and librarians, met throughout the academic year to read and discuss topics such as open access, journal economics, predatory publishing, alternative metrics (altmetrics), open data, open peer review, etc. NEXT STEPS The members of the FLC provided positive evaluations about the community and the topics about which they learned, leading the co-facilitators to run the FLC for a second year. The library’s Scholarly Communication Committee is creating and implementing a scholarly communication website utilizing the structure and content identified by the 2012-2013 FLC

Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, (2010). Freier Zugang zu Forschungsergebnissen. Bub: Forum Bibliothek Und Information, 62(1), 7.

The article reports that the research society Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) has expanded their support of open access publishing so that universities can now request that the DFG finance publication of their scientific works in open access journals.

Ottina, D. (2013). From Sustainable Publishing To Resilient Communications. Triplec (Cognition, Communication, Co-Operation): Open Access Journal For A Global Sustainable Information Society, 11(2), 604-613.

In their opening reflection on Open Access (OA) in this special section, Fuchs and Sandoval (2013) argue the current policy debate on Open Access publishing is limited by a for-profit bias which blinds it to much of the most innovative activity in Open Access. They further argue for a refocusing of the policy debate within a public service, commons based perspective of academic knowledge production. I pick up these themes by looking at another key term, sustainable publishing, in an effort to contextualize the policy debate on OA within the broader context of the privatization of the university. From this perspective, the policy debate reveals an essential tension between top-down and bottomup cultures in legitimizing knowledge. This is a tension that has profound implications for scholarly practices mediated through digital networked communications. Explicitly acknowledging this fundamental tension gives additional insight into formulating strategies for maintaining an academic culture of free and open inquiry. I suggest that the frame of resilient communications expresses the dynamic nature of scholarly communications better than that of sustainable publishing, and that empowering scholars through practice-based OA initiatives is essential in broadening grass roots support for equitable Open Access amongst scholars

Stevens, L. M. (2013). From the Editor: Getting What You Pay For? Open Access and the Future of Humanities Publishing. Tulsa Studies In Women’s Literature, 32(1), 7-21.

The article discusses the potential impact of the open access publishing movement on humanities scholarship and publishing. It is suggested that although the free circulation of knowledge is a positive goal, scholars and activists must be careful not to undermine the value of the scholarly and editorial labor which makes quality humanities publications possible. The author also suggests that authors who post their articles for open access or on university commons should pay journals a fee.

Thatcher, S. (2009). From the University Presses–Open Access and the Future of Scholarly Communication. Against the Grain, 21(5), 78-81.

The article presents a speech by the author, delivered on September 23, 2009 as part of the Andrew Neilly Lecture Series at the University of Rochester, in which he discussed open access publishing in terms of university presses and scholarly communication. He presented an overview of the history of such issues, and a forecast of likely future developments.

Dunham, G., & Walters, C. (2014). From University Press to the University’s Press: Building a One-Stop Campus Resource for Scholarly Publishing. Against The Grain, 26(6), 28-30.

The article examines the Office of Scholarly Publishing (OSP) at Indiana University (IU) in Bloomington, Indiana. Topics discussed include the role played in the OSP by Indiana University Press (IU Press), the role played by IUScholarWorks (IUSW), which is an open access publishing initiative administered by IU Libraries, and the location of the university’s publishing activities, which is the Herman B. Wells Library at IU.

Abadal, E. (2013). Gold or green: the debate on Open Access policies. International Microbiology, 16(3), 199-203. doi:10.2436/20.1501.01.194

The movement for open access to science seeks to achieve unrestricted and free access to academic publications on the Internet. To this end, two mechanisms have been established: the gold road, in which scientific journals are openly accessible, and the green road, in which publications are self-archived in repositories. The publication of the Finch Report in 2012, advocating exclusively the adoption of the gold road, generated a debate as to whether either of the two options should be prioritized. The recommendations of the Finch Report stirred controversy among academicians specialized in open access issues, who felt that the role played by repositories was not adequately considered and because the green road places the burden of publishing costs basically on authors. The Finch Report’s conclusions are compatible with the characteristics of science communication in the UK and they could surely also be applied to the (few) countries with a powerful publishing industry and substantial research funding. In Spain, both the current national legislation and the existing rules at universities largely advocate the green road. This is directly related to the structure of scientific communication in Spain, where many journals have little commercial significance, the system of charging a fee to authors has not been adopted, and there is a good repository infrastructure. As for open access policies, the performance of the scientific communication system in each country should be carefully analyzed to determine the most suitable open access strategy.

Bargheer, M., & Schmidt, B. (2008). Göttingen University Press: Publishing services in an Open Access environment. Information Services & Use, 28(2), 133-139.

The article presents a round table discussion that focuses on publishing services in an open access environment that are offered by Göttingen University Press. Begun as an additional service for the Göttingen State and University Library repository, it offers a publication consulting service on behalf of the university. It covers diverse topics such as sciences, life sciences, and humanities.

Jubb, M. (2011). Heading for the Open Road: Costs and Benefits of Transitions in Scholarly Communications. Liber Quarterly: The Journal Of European Research Libraries, 21(1), 102-124.

This paper reports on a study — overseen by representatives of the publishing, library and research funder communities in the UK — investigating the drivers, costs and benefits of potential ways to increase access to scholarly journals. It identifies five different but realistic scenarios for moving towards that end over the next five years, including gold and green open access, moves towards national licensing, publisherled delayed open access, and transactional models. It then compares and evaluates the benefits as well as the costs and risks for the UK. The scenarios, the comparisons between them, and the modelling on which they are based, amount to a benefit-cost analysis to help in appraising policy options over the next five years. Our conclusion is that policymakers who are seeking to promote increases in access should encourage the use of existing subject and institutional repositories, but avoid pushing for reductions in embargo periods, which might put at risk the sustainability of the underlying scholarly publishing system. They should also promote and facilitate a transition to gold open access, while seeking to ensure that the average level of charges for publication does not exceed circa £2,000; that the rate in the UK of open access publication is broadly in step with the rate in the rest of the world; and that total payments to journal publishers from UK universities and their funders do not rise as a consequence.

Tickell, A. (2013). Implementing Open Access in the United Kingdom. Information Services & Use, 33(1), 19-26. doi:10.3233/ISU-130688

Since July 2012, the UK has been undergoing an organized transition to open access. As of 01 April 2013, revised open access policies are coming into effect. Open access implementation requires new infrastructures for funding publishing. Universities as institutions increasingly will be central to managing article-processing charges, monitoring compliance and organizing deposit. This article reviews the implementation praxis between July 2012 and April 2013, including ongoing controversy and review, which has mainly focussed on embargo length

Hawkins, K. K. (2014). How We Pay for Publishing. Against The Grain, 26(6), 35-36.

The article examines the financial aspects of scholarly publishing. Topics discussed include the impact of these financial aspects on academic libraries and university presses, the concept of open access publishing and the financial considerations related to it, and the use of article processing charges (APC) in open access publishing.

Butler, D. (2013). Investigating journals: The dark side of publishing. Nature, 495(7442), 433-435. doi:10.1038/495433a

The article focuses on the investigation of Jeffrey Beall, academic librarian and university researcher at the University of Colorado in Denver regarding the practices of open-access publishing. It says that Beall who became a watchdog for open-access publishers criticizes them on his blog Scholarly Open Access. Beall adds that he was not prepared for the exponential growth of the occurrence of questionable publishers. The insights of publishers on the approach of Beall are also discussed.

2012 was basically the year of the predatory publisher; that was when they really exploded,” says Beall. He estimates that such outfits publish 5–10% of all open-access articles.

Beall’s list and blog are widely read by librar – ians, researchers and open-access advocates,

many of whom applaud his efforts to reveal shady publishing practices —

Wilson, K. k. (2013). Librarian vs. (Open Access) Predator: An Interview with Jeffrey Beall. Serials Review, 39(2), 125-128.

In February 2013, Kristen Wilson interviewed Jeffrey Beall, scholarly initiatives librarian at the University of Colorado Denver. Beall discusses “predatory” open access and its implications for scholarly publishing

Richard, J., Koufogiannakis, D., & Ryan, P. (2009). Librarians and Libraries Supporting Open Access Publishing. Canadian Journal Of Higher Education, 39(3), 33-48

As new models of scholarly communication emerge, librarians and libraries have responded by developing and supporting new methods of storing and providing access to information and by creating new publishing support services. This article will examine the roles of libraries and librarians in developing and supporting open access publishing initiatives and services in higher education. Canadian university libraries have been key players in the development of these services and have been bolstered by support from librarians working through and within their professional associations on advocacy and advancement initiatives, and by significant funding from the Canadian Foundation for Innovation for the Synergies initiative–a project designed to allow Canadian social science and humanities journals to publish online. The article also reflects on the experiences of three librarians involved in the open access movement at their libraries, within Canadian library associations, and as creators, managers, and editors in two new open access journals in the field of library and information studies: Evidence-based Library and Information Practice published out of the University of Alberta; and Partnership: the Canadian Journal of Library and Information Practice and Research hosted by the University of Guelph. As active participants in the creation of open access content within their own field, the authors are able to lend their experience to faculty in other disciplines and provide meaningful and responsive library service development.

Hansson, J., & Johannesson, K. (2013). Librarians’ Views of Academic Library Support for Scholarly Publishing: An Every-day Perspective. Journal Of Academic Librarianship, 39(3), 232-240. doi:10.1016/j.acalib.2013.02.002

This article reports on a study of academic librarians’ views of their work and possibilities regarding support for researchers’ publishing. Institutional repositories and Open Access are areas being dealt with in particular. Methods used are highly qualitative; data was gathered at two Swedish university libraries over a six month period through focus group interview sessions and personal logs by informants. Findings indicate that attitudes are often in collision with practicalities in the daily work in libraries. Even though they have a high degree of knowledge and awareness of scholarly publication patterns, librarians often feel insecure in the approach of researchers. There is a felt redirection in the focus of academic librarianship, from pedagogical information seeking tasks towards a more active publication support, a change which also includes a regained prominence for new forms of bibliographical work. Although there are some challenges, proactive attitudes among librarians are felt as being important in developing further support for researchers’ publishing.

Pinter, F. (2012). Open Access for Scholarly Books?. Publishing Research Quarterly, 28(3), 183-191. doi:10.1007/s12109-012-9285-0

Over the past two decades, sales of monographs have shrunk by 90 % causing prices to rise dramatically as fewer copies are sold. University libraries struggle to assemble adequate collections, and students and scholars are deprived access, especially in the developing world. Open access can play an important role in ensuring both access to knowledge and encouraging the growth of new markets for scholarly books. This article argues that by facilitating a truly global approach to funding the up-front costs of publishing and open access, there is a sustainable future for the specialist academic ‘long form publication’. Knowledge Unlatched is a new initiative that is creating an international library consortium through which publishers will be able to recover their fixed costs while at the same time reducing prices for libraries

Bauer, B., & Stieg, K. (2010). OPEN ACCESS PUBLISHING IN AUSTRIA: DEVELOPMENT AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES. Bulletin Of The Transilvania University Of Brasov, Series IV: Philology & Cultural Studies, 3(52), 271-278.

The following article provides an overview of Open Access Publishing in Austria in 2010. First of all, the participation of Austrian institutions in signing Open Access declarations and Open Access events in Austria are presented. Secondly, the article shows the development of both the Green Road to Open Access (repositories) as well as the Golden Road (Open Access Journals) in Austria. The article also describes the Open Access policies of the most important funding agency in Austria, the biggest university of the country as well as Universities Austria, the association of the 21 public universities in Austria. Finally, the paper raises the question of how Open Access is to be financed and explains the legal framework conditions for Open Access in Austria.

Nariani, R. r., & Fernandez, L. l. (2012). Open Access Publishing: What Authors Want. College & Research Libraries, 73(2), 182-195.

Campus-based open access author funds are being considered by many academic libraries as a way to support authors publishing in open access journals. Article processing fees for open access have been introduced recently by publishers and have not yet been widely accepted by authors. Few studies have surveyed authors on their reasons for publishing open access and their perceptions of open access journals. The present study was designed to gauge the uptake of library support for author funding and author satisfaction with open access publishing. Results indicate that York University authors are increasingly publishing in open access journals and are appreciative of library funding initiatives. The wider implications of open access are discussed along with specific recommendations for publishers.

Stanton, K. V., & Liew, C. L. (2011). Open Access Theses in Institutional Repositories: An Exploratory Study of the Perceptions of Doctoral Students. Information Research: An International Electronic Journal, 16(4),

We examine doctoral students’ awareness of and attitudes to open access forms of publication. Levels of awareness of open access and the concept of institutional repositories, publishing behaviour and perceptions of benefits and risks of open access publishing were explored. Method: Qualitative and quantitative data were collected through interviews with eight doctoral students enrolled in a range of disciplines in a New Zealand university and a self-completion Web survey of 251 students. Analysis: Interview data were analysed thematically, then evaluated against a theoretical framework. The interview data were then used to inform the design of the survey tool. Survey responses were analysed as a single set, then by disciple using SurveyMonkey’s online toolkit and Excel. Results: While awareness of open access and repository archiving is still low, the majority of interview and survey respondents were found to be supportive of the concept of open access. The perceived benefits of enhanced exposure and potential for sharing outweigh the perceived risks. The majority of respondents were supportive of an existing mandatory thesis submission policy. Conclusions: Low levels of awareness of the university repository remains an issue, and could be addressed by further investigating the effectiveness of different communication channels for promotion.

Mussell, J. (2013). Open Access. Journal Of Victorian Culture (Routledge), 18(4), 526-527. doi:10.1080/13555502.2013.865980

An introduction is presented to the articles within the issue on the theme of open access publishing in Great Britain during the early 2010s, including topics on the economic aspects of and the British government’s policy on open access publishing and its impact on university libraries.

Open access is not new: there is a thriving culture of open access in the sciences and

scholars in the digital humanities have been advocating open publication of research

for some time to share methods, results and data. However, the British Government’s

recent endorsement of the Finch Report (officially titled ‘Accessibility, sustainability, excellence: how to expand access to research publications: Report of the Working Group on Expanding Access to Published Research Findings’), has made open access a central concern for all researchers in UK higher education. The underlying economics and politics of journal publication arc now under scrutiny as never before.

an author-pays version of ‘gold’ open access publishing, where costs of publishing were shifted from the customer (university libraries) onto the producer (scholars), was seen by many as a way of implementing open access without disturbing the status quo. Instead of purchasing research once it has been published, universities will pay for research to be published.

While this model ensures an income stream for publishers (and it always costs something to publish), it reconfigures the relationship between scholars, their research and their institution.

The so-called ‘green’ route to publishing, where articles are made open access after their initial publication in a traditional,subscription-based journal, usually by means of deposit in an institutional repository, has focused attention on the embargo periods demanded by publishers.

Leptin, M. (2012, March 16). Open Access–Pass the Buck. Science. p. 1279.

The author reflects on open access as a model for scientific publishing. She notes that most scientists support open access despite continued controversy about the economics and political consequences of open access among various groups, including researchers, publishers, and universities. Also discussed are the financial implications of open access from the author’s point of view as an editor of the non-profit publishing group the European Molecular Biology Organization

Peters, M. A. (2009). Open Education and the Open Science Economy. Yearbook Of The National Society For The Study Of Education, 108(2), 203-225.

Openness as a complex code word for a variety of digital trends and movements has emerged as an alternative mode of “social production” based on the growing and overlapping complexities of open source, open access, open archiving, open publishing, and open science. This paper argues that the openness movement with its reinforcing structure of overlapping networks of production, access, publishing, archiving, and distribution provide an emerging architecture of alterative educational globalization not wedded to existing neoliberal forms. The open education movement and paradigm has arrived: it emerges from a complex historical background and its futures are intimately tied not only to open source, open access and open publishing movements but also to the concept of the “open society” itself which has multiple, contradictory, and contested meanings. This paper first theorizes the development and significance of “open education” by reference to the Open University, OpenCourseWare (OCW) and open access movements. The paper takes this line of argument further, arguing for a conception of “open science economy” which involves strategic international research collaborations and provides an empirical and conceptual link between university science and the global knowledge economy.

Adam, M. (2013). Open-Access-Publizieren in der Medizin – im Fokus der Bibliometrie an der SLUB Dresden. GMS Medizin-Bibliothek-Information, 13(3), 1-11. doi:10.3205/mbi000291

Since 2012, the Team Bibliometrics in the Electronic Publishing Group at the SLUB Dresden has been supporting scientists but also institutes at the Technical University Dresden in bibliometric issues. Open access (OA) publishing is one of the main topics. The recent analysis identified OA journals in the field of medicine indexed in the Web of Science (WoS) database on the basis of the Directory of Open Access Journals. Subsequently, the journal titles were examined according to their importance in the selected subject categories and the geographical distribution of editorial countries in the first part. The second part dealt with the articles in these journals and the citations contained therein. The results show an amount of 9.7 per cent of OA journals in relation to the total amount of all journals in the selected WoS subject categories. 14 per cent could be assigned to the upper quartile Q1 (Top 25 per cent). For most of the OA journals Great Britain was determined as the publishing country. The analysis of articles with German participation reveals interesting methods to obtain information in the participating authors, institutions, networks and their specific subjects. The result of citation analysis of these articles shows, that articles from traditional journals are the most cited ones.

Kersting, A., & Pappenberger, K. (2009). Promoting open access in Germany as illustrated by a recent project at the Library of the University of Konstanz. OCLC Systems & Services, 25(2), 105-113. doi:10.1108/10650750910961901

With the illustration of a best practice example for an implementation of open access in a scientific institution, the paper will be useful in fostering future open access projects. Design/methodology/approach – The paper starts with a brief overview of the existing situation of open access in Germany. The following report describes the results of a best practice example, added by the analysis of a survey on the position about open access by the scientists at the University of Konstanz. Findings – The dissemination of the advantages of open access publishing is fundamental for the success of implementing open access in a scientific institution. For the University of Konstanz, it is shown that elementary factors of success are an intensive cooperation with the head of the university and a vigorous approach to inform scholars about open access. Also, some more conditions are essential to present a persuasive service: The Library of the University of Konstanz offers an institutional repository as an open access publication platform and hosts open journal systems for open access journals. High-level support and consultation for open access publishing at all administrative levels is provided. The integration of the local activities into national and international initiatives and projects is pursued for example by the joint operation of the information platform open-access.net. Originality/value – The paper offers insights in one of the most innovative open access projects in Germany. The University of Konstanz belongs to the pioneers of the open access movement in Germany and is currently running a successful open access project.

Beals, M. H. (2013). Rapunzel and the Ivory Tower: How Open Access Will Save the Humanities (from Themselves). Journal Of Victorian Culture (Routledge), 18(4), 543-550. doi:10.1080/13555502.2013.865977

The author argues in favor of open access publishing, contending that it will bridge university academics and academic scholarship’s relationship with the public sphere. An overview of open access publishing’s impact on academic journals, including in regard to periodical subscriptions, membership fees and the discourse on history within society, is provided. An overview of digital access to open access publishing is also provided.

crisis of authorship has centred on the charging of Article Processing Charges (APCs) and how best to accommodate the shift from pay-to-read to pay-to-publish models.

Pochoda, P. (2008). Scholarly Publication at the Digital Tipping Point. Journal Of Electronic Publishing, 11(2), 8.

The article presents information on a joint publishing project “Digitalculturebooks” between the University of Michigan Press and the Scholarly Publishing Office of Michigan University Library in Michigan. The aim of the project was to publish books about new media in a printed version and an open access (OA) online version. It is mentioned that the project not only intended to publish innovative and accessible work about the social, cultural, and political impact of new and to collect data about the variation in reading habits and preferences across different scholarly reading communities, but also to explore the opportunities and the obstacles involved in a press working in a partnership with a technologically abled library unit with a business model.

Scientific Publishing: the Dilemma of Research Funding Organisations. (2009). European Review, 17(1), 23-31.

Present changes in scientific publishing, especially those summarised by the term ?Open Access? (OA), may ultimately lead to the complete replacement of a reader-paid to an author, or funding-paid, publication system. This transformation would shift the financial burden for scientific publishing from the Research Performing Organisations (RPOs), particularly from scientific libraries, universities, etc, to the Research Funding Organisations (RFOs). The transition phase is difficult; it leads to double funding of OA publications (by subscriptions and author-sponsored OA) and may thus increase the overall costs of scientific publishing. This may explain why ? with a few exceptions ? RFOs have not been at the forefront of the OA paradigm in the past. In 2008, the General Assembly of EUROHORCs, the European organisation of the heads of research councils, agreed to recommend to its member organisations at least a minimal standard of Open Access based on the Berlin Declaration of 2003 (green way of OA). In the long run, the publishing system needs some fundamental changes to reduce the present costs and to keep up its potential. In order to design a new system, all players have to cooperate and be ready to throw overboard some old traditions, lovable as they may be.

Kennan, M. A. (2010). The economic implications of alternative publishing models: views from a non-economist. Prometheus, 28(1), 85-89. doi:10.1080/08109021003676391

In this article the author discusses economic aspects of alternative economic models for scholarly publishing with reference to a report by J. Houghton and C. Oppenheim. The author present information on the economic models discussed in Houghton and Oppenheim report to the Great Britain’s Joint Information Systems Committee (JISC). He discusses the open access (OA) publishing and suggests that mandates should be made by universities for OA.

I cannot respond to their paper in either of these roles. Instead, I propose to respond both as an academic who conducts research, writes about it and tries to get it published, and as a researcher interested in scholarly communication, publishing and open access.

To continue with a system (of scholarly publishing or anything else) without regularly investigating and analyzing the alternatives, is neither common sense nor scholarly.

Hawkins, K. S. (2014). The Evolution of Publishing Agreements at the University of Michigan Library. Journal Of Librarianship & Scholarly Communication, 2(4), 90-94. doi:10.7710/2162-3309.1175

Taking as an example an open-access journal with a single editor, this article discusses the various configurations of rights agreements used by the University of Michigan Library throughout the evolution of its publishing operation, the advantages of the various models, and the reasons for moving from one to another.

Bankier, J., & Perciali, I. (2008). The Institutional Repository Rediscovered: What Can a University Do for Open Access Publishing?. Serials Review, 34(1), 21-26. doi:10.1016/j.serrev.2007.12.003

Universities have always been one of the key players in open access publishing and have encountered the particular obstacle that faces this Green model of open access, namely, disappointing author uptake. Today, the university has a unique opportunity to reinvent and to reinvigorate the model of the institutional repository. This article explores what is not working about the way we talk about repositories to authors today and how can we better meet faculty needs. More than an archive, a repository can be a showcase that allows scholars to build attractive scholarly profiles, and a platform to publish original content in emerging open-access journals. Serials Review 2008; 34:21-26.

Collister, L. B., Deliyannides, T. S., & Dyas-Correia, S. (2014). The Library as Publisher. Serials Librarian, 66(1-4), 20-29.

This article describes a half-day preconference that focused on the library as publisher. It examined how the movement from print to online publication has impacted the roles of libraries and their ability to take on new roles as publishers. The session explored the benefits of libraries becoming publishers, and discussed Open Access, what it is and is not and its importance to libraries and scholarly communication. A detailed case study of the publishing operations of the University Library System at the University of Pittsburgh was presented as an example of a successful library publishing program. The session provided an opportunity for participants to discover ways that libraries can be involved in publishing

OA literature is digital, online, free of charge, and free of most copyright and licensing restrictions. OA works are still covered by copyright law, but spe- cial license terms such as Creative Commons licenses are applied to allow sharing and reuse. All major OA initiatives for scientific and scholarly litera- ture insist on the importance of peer review. OA is therefore compatible with copyright, peer review, revenue (even profit), print, preservation, prestige,

quality, career advancement, indexing, and supportive services associated with conventional scholarly literature. OA is not Open Source, which applies to computer software, nor Open Content, which applies to non-scholarly content, nor Open Data, which is a movement to support sharing of research data, nor free access, which carries no monetary charges for access, yet all rights may be reserved.

Changing laws, like the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) and the Research Works Act, as well as the Google Books copyright settlement and its aftermath, have also had an important impact on scholarly communication.

The changing scholarly communication environment has led to chang- ing economic models, including the advent of the “Big Deal” for the purchaseof journals and e-books, the creation of the pay-per-view model and other alternative purchasing models. It has also led to the creation of OA publish- ing models, the Hybrid OA publishing model, and self-publishing. Today,

over 150 universities around the world mandate OA deposits of faculty works and the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ) lists 9,437 OA journals in 119 countries.The Directory of Open Access Repositories (OpenDOAR) lists 2,284 open archives in 103 countries.

Potvin, S. (2013). The Principle and the Pragmatist 1 [1] The title draws on David Lewis’s comment: “Open access journals claim two advantages: the first is pragmatic and the second is principled.” See David W. Lewis, “The Inevitability of Open Access,” College &Research Libraries 73:5 (September 2012): 493–506. : On Conflict and Coalescence for Librarian Engagement with Open Access Initiatives. Journal Of Academic Librarianship, 39(1), 67-75.

This article considers Open Access (OA) training and the supports and structures in place in academic libraries in the United States from the perspective of a new librarian. OA programming is contextualized by the larger project of Scholarly Communication in academic libraries, and the two share a historical focus on journal literature and a continued emphasis on public access and the economics of scholarly publishing. Challenges in preparing academic librarians for involvement with OA efforts include the evolving and potentially divergent nature of the international OA movement and the inherent tensions of a role with both principled and pragmatic components that serves a particular university community as well as a larger movement.

Bastos, F., Vidotti, S., & Oddone, N. (2011). The University and its libraries: Reactions and resistance to scientific publishers. Information Services & Use, 31(3/4), 121-129.

This paper addresses the relationship of copyright and the right of universities on scientific production. Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) are causing many changes in the system of scientific communication, such as the creation of Institutional Repositories that aim to gather scientific production in digital format. The University needs quicker ways of spreading academic production and many questions are emerging due to contexts such as the Open Access movement. Thus, this paper questions the positioning of Universities, especially Public Universities, which despite having policies related to intellectual property to protect the transferring forms of research results to society; many times do not have a positioning or a mechanism that regulates the self-deposit of scientific production in these Institutional Repositories. In order to develop this paper, the following issues are addressed: lack of interest of the University in storing scientific production; reports on the relationship of the library with scientific publishing houses; the participation of faculty members and students in supporting the Free Access movement; and initiatives aimed at greater flexibility of copyright to the context of scientific production. In order to follow the development of these issues at international level, it was opted for qualitative research with non-participating direct observation to carry out the identification and description of copyright policy of important publishers from the ROMEO SHERPA site; therefore, it can be observed that there are changes regarding the publishers’ flexibility before self-archiving of authors in open access institutional repositories in their universities. Given this scenario, we present reflections and considerations that involve the progress and mainly the integration of the University and its faculty members; the institution should recommend and guide its faculty members not to transfer their copyrights, but to defend their right of copy to Institutional Repositories along with Publishing Houses

Jagodzinski, C. M. (2008). The University Press in North America: A Brief History. Journal Of Scholarly Publishing, 40(1), 1-20. doi:10.3138/jsp.40.1.1

Simon-Ritz, F. (2012). Warten auf die Wissenschaftsschranke. Bub: Forum Bibliothek Und Information, 64(9), 562-564.

An article on the debate over copyright law and Open Access publishing in Germany is presented. The author describes the demands for noncommercial secondary usage rights by schools, libraries, and universities, as well as detailing the sections of the copyright laws which he considers most damaging to the larger research community

O’Donnell, M. P. (2014). What is the future of scholarly journals in an open access environment?. American Journal Of Health Promotion, 29(1), v-vi. doi:10.4278/ajhp.29.1.v

This editorial provides an overview of journey of the journal American Journal of Health Promotion. This journal would continue to be allowed to publish these articles but wanted me to understand the public would also have free access to them online. This university was following the lead of the Harvard Law School Open Access Policy, which was adopted by faculty at Harvard and Stanford in 2008, at MIT in 2009, and at many other prestigious universities and colleges since then. The traditional publishers want to maximize subscriber satisfaction so they can sell more subscriptions and minimize the number of accepted manuscripts to reduce the cost of printing, whereas the fee-based online publishers want to increase the number of accepted manuscripts to maximize publishing fees. The cost of this subscription is $895/y. The subscription must be in place before the article is typeset.

Armato, D. (2012). What Was a University Press?. Against The Grain, 24(6), 58-62.

Hall, R. (2014). You Say You Want a Publishing Revolution. Progressive Librarian, (43), 35-46.

A recent study published in PLoS ONE estimated that 27 million, or 24%, of the 114 million English-language scholarly documents available through Google Scholar and Microsoft Academic Search are freely available on the web (Khabsa & Giles, 2014). While this is not nearly as much as open access advocates would like, it shows a significant step in the right direction. Though the authors of this study fail to acknowledge the sources of this free

information, it can be surmised that library publishing initiatives—including open access journals and institutional repositories—have contributed greatly.

Boulder Faculty Teaching with Technology Report

Sarah Wise, Education Researcher , Megan Meyer, Research Assistant, March 8,2016

http://www.colorado.edu/assett/sites/default/files/attached-files/final-fac-survey-full-report.pdf

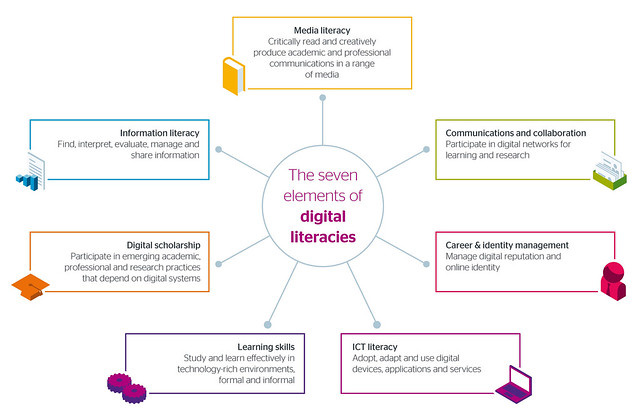

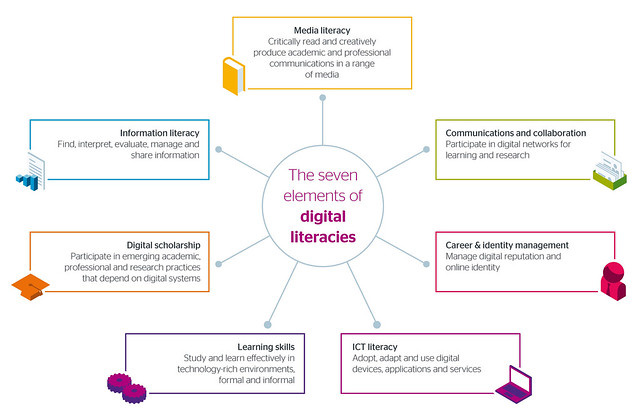

Faculty perceive undergraduates to be less proficient with digital literacy skills. One-third think

their students do not find or organize digital information very well. The majority (52%) think

they lack skill in validating digital information.

My note: for the SCSU librarians, digital literacy is fancy word for information literacy. Digital literacy, as used in this report is much greater area, which encompasses much broader set of skills

Faculty do not prefer to teach online (57%) or in a hybrid format (where some sessions occur

online, 32%). One-third of faculty reported no experience with these least popular course types

my note: pay attention to the questions asked; questions I am asking Mike Penrod to let me work with faculty for years. Questions, which are snubbed by CETL and a dominance of D2L and MnSCU mandated tools is established.

Table 5. Do you use these in-class technologies for teaching undergraduates? Which are the Top 3 in-class technologies you would like to learn or use more? (n = 442)

|

Top 3 |

use in most of my classes |

have used in some classes |

tried, but do not use |

N/A: no experience |

| in-class activities, problems (via worksheets, tablets, laptops, simulations, beSocratic, etc.) |

52% |

33% |

30% |

6% |

30% |

| in-class question, discussion tools (e.g. Twitter, TodaysMeet, aka “backchannel communication”) |

47% |

8% |

13% |

11% |

68% |

| using online resources to find high quality curricular materials |

37% |

48% |

31% |

3% |

18% |

| iClickers |

24% |

23% |

16% |

9% |

52% |

| other presentation tool (Prezi, Google presentation, Slide Carnival, etc.) |

23% |

14% |

21% |

15% |

51% |

| whiteboard / blackboard |

20% |

58% |

23% |

6% |

14% |

| Powerpoint or Keynote |

20% |

74% |

16% |

4% |

5% |

| document camera / overhead projector |

15% |

28% |

20% |

14% |

38%

|

Table 6. Do you have undergraduates use these assignment technology tools? Which are your Top 3 assignment technology tools to learn about or use more? (n = 432)

|

Top 3 |

use in most of my classes |

have used in some classes |

tried, but do not use |

N/A: no experience using |

| collaborative reading and discussion tools (e.g. VoiceThread, NB, NotaBene, Highlighter, beSocratic) |

43% |

3% |

10% |

10% |

77% |

| collaborative project, writing, editing tools (wikis, PBWorks, Weebly, Google Drive, Dropbox, Zotero) |

38% |

16% |

29% |

12% |

43% |

| online practice problems / quizzes with instant feedback |

36% |

22% |

22% |

8% |

47% |

| online discussions (D2L, Today’s Meet, etc) |

31% |

33% |

21% |

15% |

30% |

| individual written assignment, presentation and project tools (blogs, assignment submission, Powerpoint, Prezi, Adobe Creative Suite, etc.) |

31% |

43% |

28% |

7% |

22% |

| research tools (Chinook, pubMed, Google Scholar, Mendeley, Zotero, Evernote) |

30% |

33% |

32% |

8% |

27% |

| online practice (problems, quizzes, simulations, games, CAPA, Pearson Mastering, etc.) |

27% |

20% |

21% |

7% |

52% |

| data analysis tools (SPSS, R, Latex, Excel, NVivo, MATLAB, etc.) |

24% |

9% |

23% |

6% |

62% |

| readings (online textbooks, articles, e-books) |

21% |

68% |

23% |

1% |

8% |

Table 7. Do you use any of these online tools in your teaching? Which are the Top 3 online tools you would like to learn about or use more? (n = 437)

|

Top 3 |

use in most of my classes |

have used in some classes |

tried, but do not use |

N/A: no experience using |

| videos/animations produced for my course (online lectures, Lecture Capture, Camtasia, Vimeo) |

38% |

14% |

21% |

11% |

54% |

| chat-based office hours or meetings (D2L chat, Google Hangouts, texting, tutoring portals, etc.) |

36% |

4% |

9% |

10% |

76% |

| simulations, PhET, educational games |

27% |

7% |

17% |

6% |

70% |

| videoconferencing-based office hours or meetings (Zoom, Skype, Continuing Education’s Composition hub, etc.) |

26% |

4% |

13% |

11% |

72% |

| alternative to D2L (moodle, Google Site, wordpress course website) |

23% |

11% |

10% |

13% |

66% |

| D2L course platform |

23% |

81% |

7% |

4% |

8% |

| online tutorials and trainings (OIT tutorials, Lynda.com videos) |

21% |

4% |

16% |

13% |

68% |

| D2L as a portal to other learning tools (homework websites, videos, simulations, Nota Bene/NB, Voice Thread, etc.) |

21% |

28% |

18% |

11% |

42% |

| videos/animations produced elsewhere |

19% |

40% |

36% |

2% |

22% |

In both large and small classes, the most common responses faculty make to digital distraction are to discuss why it is a problem and to limit or ban phones in class.

my note: which completely defies the BYOD and turns into empty talk / lip service.

Quite a number of other faculty (n = 18) reported putting the onus on themselves to plan engaging and busy class sessions to preclude distraction, for example:

“If my students are more interested in their laptops than my course material, I need to make my curriculum more interesting.”

I have not found this to be a problem. When the teaching and learning are both engaged/engaging, device problems tend to disappear.”

The most common complaint related to students and technology was their lack of common technological skills, including D2L and Google, and needing to take time to teach these skills in class (n = 14). Two commented that digital skills in today’s students were lower than in their students 10 years ago.

Table 9. Which of the following are the most effective types of learning opportunities about teaching, for you? Chose your Top 2-3. (n = 473)

Count Percentage

| meeting 1:1 with an expert |

296 |

63% |

| hour-long workshop |

240 |

51% |

| contact an expert on-call (phone, email, etc) |

155 |

33% |

| faculty learning community (meeting across asemester,

e.g. ASSETT’s Hybrid/Online Course Design Seminar) |

116 |

25% |

| expert hands-on support for course redesign (e.g. OIT’s Academic Design Team) |

114 |

24% |

| opportunity to apply for grant funding with expert support, for a project I design (e.g. ASSETT’s Development Awards) |

97 |

21% |

| half-day or day-long workshop |

98 |

21% |

| other |

40 |

8% |

| multi-day retreats / institutes |

30 |

6% |

Faculty indicated that the best times for them to attend teaching professional developments across the year are before and early semester, and summer. They were split among all options for meeting across one week, but preferred afternoon sessions to mornings. Only 8% of respondents (n = 40) indicated they would not likely attend any professional development session (Table 10).

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Teaching Through Technology

Table T1: Faculty beliefs about using digital technologies in teaching

|

Count |

Column N% |

| Technology is a significant barrier to teaching and learning. |

1 |

0.2% |

| Technology can have a place in teaching, but often detracts from teaching and learning. |

76 |

18.3% |

| Technology has a place in teaching, and usually enhances the teaching learning process. |

233 |

56.0% |

| Technology greatly enhances the teaching learning process. |

106 |

25.5% |

Table T2: Faculty beliefs about the impact of technology on courses

|

Count |

Column N% |

| Makes a more effective course |

302 |

72.6% |

| Makes no difference in the effectiveness of a course |

42 |

10.1% |

| Makes a less effective course |

7 |

1.7% |

| Has an unknown impact |

65 |

15.6% |

Table T3: Faculty use of common technologies (most frequently selected categories shaded)

|

Once a month or less |

A few hours a month |

A few hours a week |

An hour a day |

Several hours a day |

| Count |

% |

Count |

% |

Count |

% |

Count |

% |

Count |

% |

| Computer |

19 |

4.8% |

15 |

3.8% |

46 |

11.5% |

37 |

9.3% |

282 |

70.7% |

| Smart Phone |

220 |

60.6% |

42 |

11.6% |

32 |

8.8% |

45 |

12.4% |

24 |

6.6% |

| Office Software |

31 |

7.8% |

19 |

4.8% |

41 |

10.3% |

82 |

20.6% |

226 |

56.6% |

| Email |

1 |

0.2% |

19 |

4.6% |

53 |

12.8% |

98 |

23.7% |

243 |

58.7% |

| Social Networking |

243 |

68.8% |

40 |

11.3% |

40 |

11.3% |

23 |

6.5% |

7 |

2.0% |

| Video/Sound Media |

105 |

27.6% |

96 |

25.2% |

95 |

24.9% |

53 |

13.9% |

32 |

8.4% |

Table T9: One sample t-test for influence of technology on approaches to grading and assessment

|

Test Value = 50 |

| t |

df |

Sig. (2-tailed) |

Mean Difference |

95% Confidence Interval of the Difference |

| Lower |

Upper |

| In class tests and quizzes |

-4.369 |

78 |

.000 |

-9.74684 |

-14.1886 |

-5.3051 |

| Online tests and quizzes |

5.624 |

69 |

.000 |

14.77143 |

9.5313 |

20.0115 |

| Ungraded assessments |

1.176 |

66 |

.244 |

2.17910 |

-1.5208 |

5.8790 |

| Formative assessment |

5.534 |

70 |

.000 |

9.56338 |

6.1169 |

13.0099 |

| Short essays, papers, lab reports, etc. |

2.876 |

70 |

.005 |

5.45070 |

1.6702 |

9.2312 |

| Extended essays and major projects or performances |

1.931 |

69 |

.058 |

3.67143 |

-.1219 |

7.4648 |

| Collaborative learning projects |

.000 |

73 |

1.000 |

.00000 |

-4.9819 |

4.9819 |

Table T10: Rate the degree to which your role as a faculty member and teacher has changed as a result of increased as a result of increased use of technology

|

Strongly Disagree |

Disagree |

Somewhat Disagree |

Somewhat Agree |

Agree |

Strongly Agree |

| Count |

% |

Count |

% |

Count |

% |

Count |

% |

Count |

% |

Count |

% |

| shifting from the role of content expert to one of learning facilitator |

12 |

9.2% |

22 |

16.9% |

14 |

10.8% |

37 |

28.5% |

29 |

22.3% |

16 |

12.3% |

| your primary role is to provide content for students |

14 |

10.9% |

13 |

10.1% |

28 |

21.7% |

29 |

22.5% |

25 |

19.4% |

20 |

15.5% |

| your identification with your University is increased |

23 |

18.3% |

26 |

20.6% |

42 |

33.3% |

20 |

15.9% |

12 |

9.5% |

3 |

2.4% |

| you have less ownership of your course content |

26 |

20.2% |

39 |

30.2% |

24 |

18.6% |

21 |

16.3% |

14 |

10.9% |

5 |

3.9% |

| your role as a teacher is strengthened |

13 |

10.1% |

12 |

9.3% |

26 |

20.2% |

37 |

28.7% |

29 |

22.5% |

12 |

9.3% |

| your overall control over your course(s) is diminished |

23 |

17.7% |

44 |

33.8% |

30 |

23.1% |

20 |

15.4% |

7 |

5.4% |

6 |

4.6% |

Table T14: One sample t-test for influence of technology on faculty time spent on specific teaching activities

|

|

Test Value = 50 |

| t |

df |

Sig. (2-tailed) |

Mean Difference |

95% Confidence Interval of the Difference |

| Lower |

Upper |

| Lecturing |

-7.381 |

88 |

.000 |

-12.04494 |

-15.2879 |

-8.8020 |

| Preparing course materials |

9.246 |

96 |

.000 |

16.85567 |

13.2370 |

20.4744 |

| Identifying course materials |

8.111 |

85 |

.000 |

13.80233 |

10.4191 |

17.1856 |

| Grading / assessing |

5.221 |

87 |

.000 |

10.48864 |

6.4959 |

14.4813 |

| Course design |

12.962 |

94 |

.000 |

21.55789 |

18.2558 |

24.8600 |

| Increasing access to materials for all types of learners |

8.632 |

86 |

.000 |

16.12644 |

12.4126 |

19.8403 |

| Reading student discussion posts |

10.102 |

79 |

.000 |

21.98750 |

17.6553 |

26.3197 |

| Email to/with students |

15.809 |

93 |

.000 |

26.62766 |

23.2830 |

29.9724 |

++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Study of Faculty and Information Technology, 2014

http://net.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/ers1407/ers1407.pdf

Although the LMS is pervasive in higher education, 15% of faculty said that they

do not use the LMS at all. Survey demographics suggest these nonusers are part of